This essay was written as a summative part of my undergraduate studies at the London School of Economics.

In 1997, the ‘Bank of England’ was granted independence and tasked with maintaining price stability in the UK. At the same time, the Bank’s regulatory responsibilities were removed, and the ‘Financial Services Authority’ (‘FSA’) was formed.

The ‘Financial Crisis’, prompted changes to the FSA’s powers. The Labour Government granted it extra responsibilities in the Financial Services Act 2010, including a focus on financial stability. Six-months later, a general election and a new ‘Coalition Government’, decided to dissolve the FSA, and replace the old regulatory structure with an entirely new set of bodies (Financial Services Act 2012).

This paper explores the arguments used during these two phases of regulatory reform. I use content analysis of Parliamentary debates to understand the causes of these policy changes, arguing that the critical junctures thesis is inappropriate for explaining the existence of the 2012 Act as it relies on the notion of policy failure. After establishing a theoretical framework, and outlining my methodology, I detail my analysis, and find evidence in support of the hypothesis. I conclude that partisan political pay-offs drove the case for reform, rather than pure policy failure.

Theoretical Framework

The FSA was the first instance of a single financial services regulatory body in a global financial centre, and was responsible for prudential, business and market conduct regulation for the entire UK financial sector (Briault, 1999). Its creation was prompted by the increasing complexity of the financial sector and it was argued that the FSA would provide the “standard of supervision […] that the public has a right to expect,” (Joint Committee on Financial Services and Markets, 1999:99). But the 2007 Financial Crisis exposed the FSA as an apparent policy failure.

The critical junctures thesis posits a three-stage cycle of change — policy failure, paradigm shift, and emulation (King, 2005). Prior research suggests that during times of political or economic crisis, ‘policy entrepreneurs’ will suggest alternative policy solutions and try to cause a ‘policy paradigm shift’ (Hall & Taylor, 1996; Marcussen, 2005; King, 2005). The 2010 Act could be considered a paradigm shift responding to a ‘critical juncture’. This is the puzzle. The Act reforming the FSA came into effect in the same year that the Conservative-led Coalition Government committed to abolishing it (Coalition Agreement, 2010). Policy failure is a necessary condition for policy change in this theory, but no additional policy failure seemed to have occurred in this period to prompt a second paradigm shift (i.e. the 2012 Act) — it was too soon to know the impact of the previous changes.

At a time of policy failure, actors seek to find optimal solutions to policy problems, and ineffective structures will be dismantled (Moser, 1999; Marcussen, 2005); the fact that the FSA was initially reformed – not abolished – suggests it was seen as an optimal solution. Research also suggests that institutions have path dependency and ‘lock in’ preventing actors from reversing the decisions of previous incumbents (North, 1990; Boettke et al. 2008; Pierson, 2000a, 2000b). Given the apparent lack of policy failure, and rigidity of institutions, the critical junctures thesis seems to be missing a key component in explaining this particular paradigm shift. That component may be electoral pay-offs.

Financial regulation can be considered a ‘high-risk’ principal-agent problem; the costs of getting the delegation ‘wrong’ are high, not only in terms of economic, but also electoral costs — lots of research evidences a link between public perceptions of a government’s economic record, and electoral outcomes (Chubb, 1988; van der Brug et al. 2007); these costs are severe. Politicians will want to ensure that regulatory delegation is optimal, and maximises the electoral pay-off — or at least minimises losses if policy fails, through blame switching (Alesina & Tabellini, 2005; Fiorina, 1977).

As politicians are necessarily office-seeking (Downs, 1957; Riker, 1962), we can assume that, when policy fails, parties might pursue partisan tactics in order to discredit their opposition.

Hypothesis: The decision to dissolve the FSA was not caused by policy failure, but instead was driven by partisan electoral incentives.

In this instance, the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties should seek to discredit the Labour Party’s economic record to boost their own electoral pay-offs. This should occur regardless of the effectiveness of previous legislation, as, like in other areas of policy, politicians have short-term time-horizons and will act in their short-term electoral interests, even at long-term cost to the polity (Kydland & Prescott, 1977; Moser, 1999; Gilardi, 2007).

Methodology

| Transcript | Date |

|---|---|

| Oral Answers to Questions, Treasury (Financial Services (Regulation)) | Nov 30, 2009 |

| Financial Services Act 2010 — Second Reading | Nov 30, 2009 |

| Financial Services Act 2010 — Third Reading | Jan 25, 2010 |

| Urgent Question: Alistair Darling MP (Financial Services Regulation) | Jun 16, 2010 |

| Statement: Mark Hoban MP (Banking Reform) | Jun 17, 2010 |

| Financial Services Act 2012 — Second Reading | Feb 6, 2012 |

| Financial Services Act 2012 — Third Reading | May 22, 2012 |

I employ automated content analysis, using the Alceste software package, to analyse two sets of transcripts from the UK House of Commons, one prior to the 2010 Act, and another prior to the 2012 Act (Table 1). Speeches are likely to be most representative of actors’ motivations, and provide sufficiently reliable data for analysis. Comparing each set of debates allows us to assess motivations over time and test the hypothesis, which, if accurate, should show rhetoric as a prominent feature throughout the debates.

The exact way that Alceste completes the analysis has been extensively detailed (cf. Bailey & Schonhardt-Bailey, 2008; 2010; Schonhardt-Bailey, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2012; Schonhardt-Bailey et al., 2012) but it can be considered a complete methodology due to the combination of “sophisticated statistical methods” to produce its results (Kronberger & Wagner, 2000:306). Simplistically, the software finds co-occurrences of language from a set of sampling units (‘Initial Contextual Units’ or ICUs; represented here by each change in speaker), based on sentence structure and word use (‘Elementary Contextual Units’ or ‘ECUs’), such that each topic (‘lexical class’) is as statistically unique as possible (ibid). Each ECU and word form, (and any passive variable assigned by the researcher) is assigned a Chi2 value, representing significance (Table 2). Higher value ECUs and word forms are most representative of their classes, and can be considered important in the context of the whole corpus. This is Alceste’s main methodological contribution — it can show which parts of the debate are most significant, and thus which parts are likely to be most influential and representative of actors’ motivations.

| Significance | Chi2 value |

|---|---|

| Not significant | less than 2.71 |

| 10% | less than 3.84 |

| 5% (*) | less than 6.63 |

| 1% (**) | less than 10.80 |

| <1% (***) | more than 10.80 |

Findings

| 2010 Act | 2012 Act | |

|---|---|---|

| Word count | 42,402 | 66,949 |

| Unique words analysed | 1,873 | 5,104 |

| ICUs | 115 | 282 |

| Classified ECUs | 889 (81.68%) | 1,132 (65.13%) |

| Lexical classes | 4 | 3 |

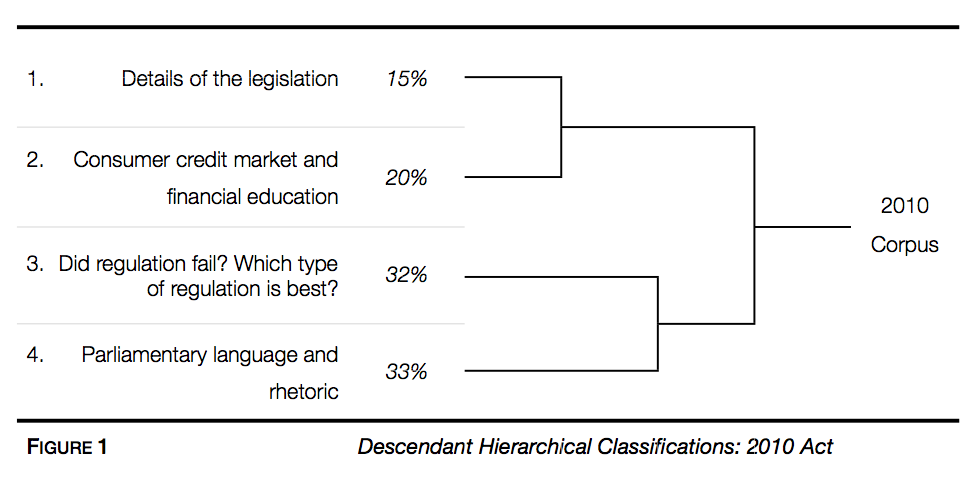

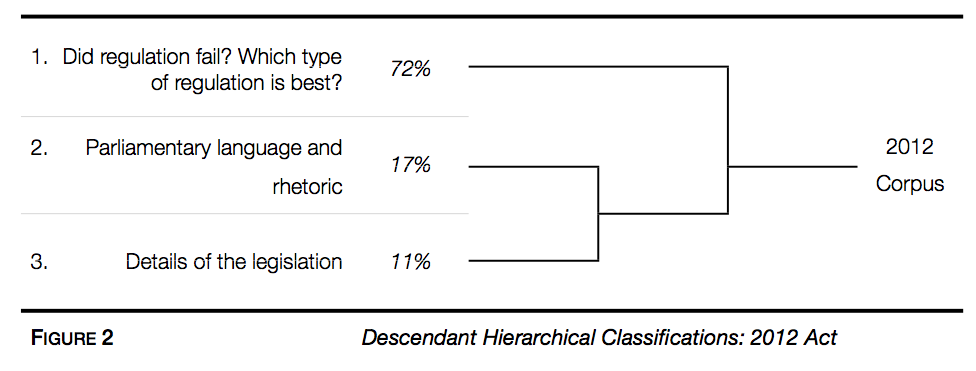

Over 100,000 words were analysed across 397 instances of speech; Table 3 shows the basic results. Whilst the 2010 Act corpus is smaller than the 2012 Act, both attain reasonably robust classifications (82% and 65%). Figures 1-2 show the ‘descendant hierarchical classifications’; these map how closely each class is related to another. An analysis of the most significant word forms and ECUs for each class reveals similar topics of discussion running across both corpora. Classes 1, 3, and 4 in the 2010 corpus, broadly equate to Classes 3, 1, and 2 respectively in the 2012 corpus — though the size of each class is quite different. One class — ‘Consumer credit market and financial education’ — is missing from the latter corpus. One likely explanation for this is the significant amount of lobbying and media attention given to financial education during this period (cf. BBC News, 2010). This was absent from the 2012 Act debates. Some characteristic ECUs for this class include:

better protect the taxpayer; importantly, restore consumers’ confidence in financial services by providing people with greater protection and education […]

(2010 corpus, Cl.2)

Citizens Advice welcomes the establishment of the consumer financial education body, saying that it is a step change that will benefit consumers enormously.

(2010 corpus, Cl.2)

Overall, the class speaks very little to the hypothesis and can be discounted from the analysis. The 2012 corpus sees more focus on how regulation contributed to the Crisis, and how it should be reformed (72% compared to 32%). At the same time, almost one-third less discussion focuses on the details of the legislation. This shows a shift in the kind of debate occurring during these two phases.

The 2010 corpus is far more confrontational from the Conservatives, but based in evidence. Many of the ECUs highlight the 2010 Act as simple rebranding of the existing regulatory framework:

The Treasury Committee […] said that the proposals are a “largely cosmetic measure”, and that “merely rebranding the tripartite standing committee will do little in itself”.

(Osborne, 2010 corpus)

[…] Jacques De Larosiare has said explicitly about the Conservative proposals — that he supports them. The Bundesbank in Germany is now taking control of prudential regulation of banking, and the Belgian Central Bank is doing the same.

(Osborne, 2010 corpus)

If countries all over the world are learning the lesson that central banks have to be deeply involved in prudential supervision, we should learn it in the United Kingdom.

(Osborne, 2010 corpus)

The language in this class is clearly and deliberately partisan, but it is also mostly based in fact and evidence. It highlights the Labour Government’s refusal to accept the new orthodoxy, but focus is on institutional, not political failure. This seems to support the critical junctures thesis — a paradigm shift has occurred in the debate and the focus is on policy failure.

This type of argumentation disappears in the 2012 corpus and is replaced by rhetoric highlighting Labour’s incompetence. This is exhibited in the ‘Parliamentary language and rhetoric’ class. Much of this class can be safely discounted from the analysis; it is dominated by language unique to the style of debate in the UK Parliament:

It is a pleasure to follow the eloquent contribution of the Hon. Member for Leeds East (Mr. Mudie). He declared to the house that he had dropped his speech, but I do not think that anyone noticed.

(2012 corpus, Cl.2)

The remainder of the 2012 corpus sees members mocking the Labour Party over claims that they eradicated ‘boom-and-bust’ economics. These only attain high significance in this corpus, and are clearly aimed at discrediting the opposition Labour Party.

Will the Chancellor assure the House and the country that he will never display the sort of complacency so aptly demonstrated by the Right Hon. Member for Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath (Mr. Brown), who said in 2007 that we were entering a golden age of prosperity in the City of London?

(2012 corpus, Cl.2)

These comments come from back-bench MPs, and government ministers alike. Moreover, these are the most significant ECUs in this class — at the 1% level; they are prominent and important to the context of the debates as a whole. This is certainly an indication that the coalition parties — but in particular the Conservatives — sought to use the 2012 Act as a way of further ridiculing the previous government’s economic record. Very few ECUs touch on institutional and policy failure as the impetus for reform; the most significant parts of the discussion are focused purely on the record of the previous government.

Overall, the ECUs point to a narrative of undermining the Labour Party on the intellectual arguments pre-election and through rhetoric post-election. This is inconsistent with the critical junctures thesis, which sees policy failure as a necessary condition — no one really discusses policy failure at all here. It is, however, consistent with my hypothesis, which suggests that electoral incentives and partisan politics drove this second wave of reform.

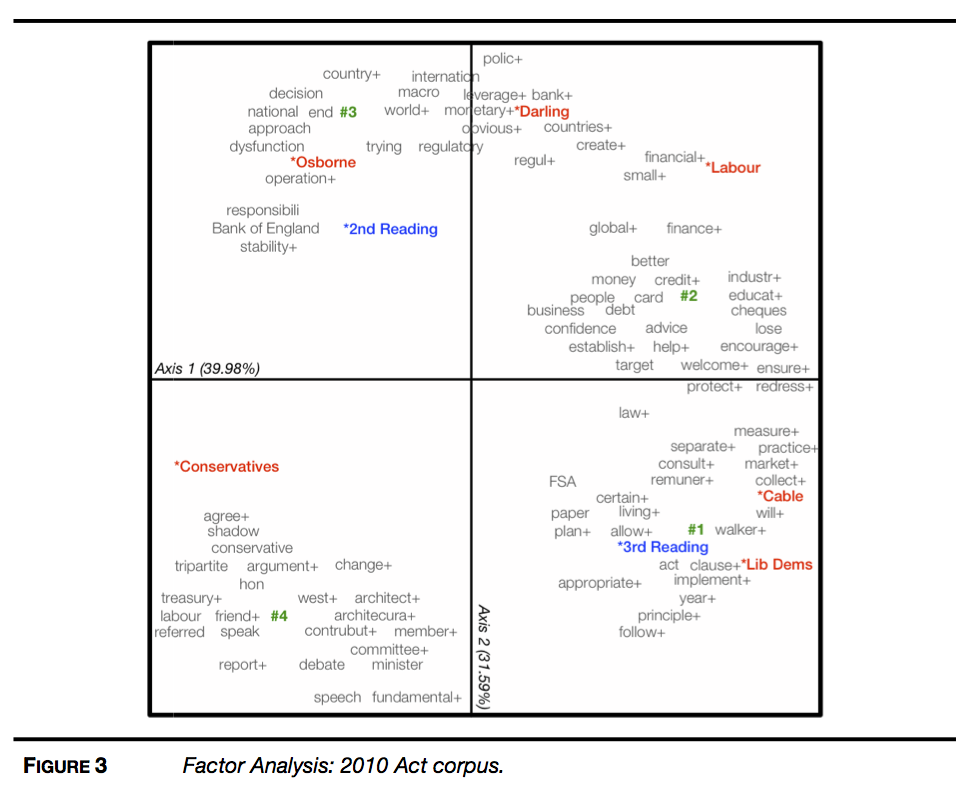

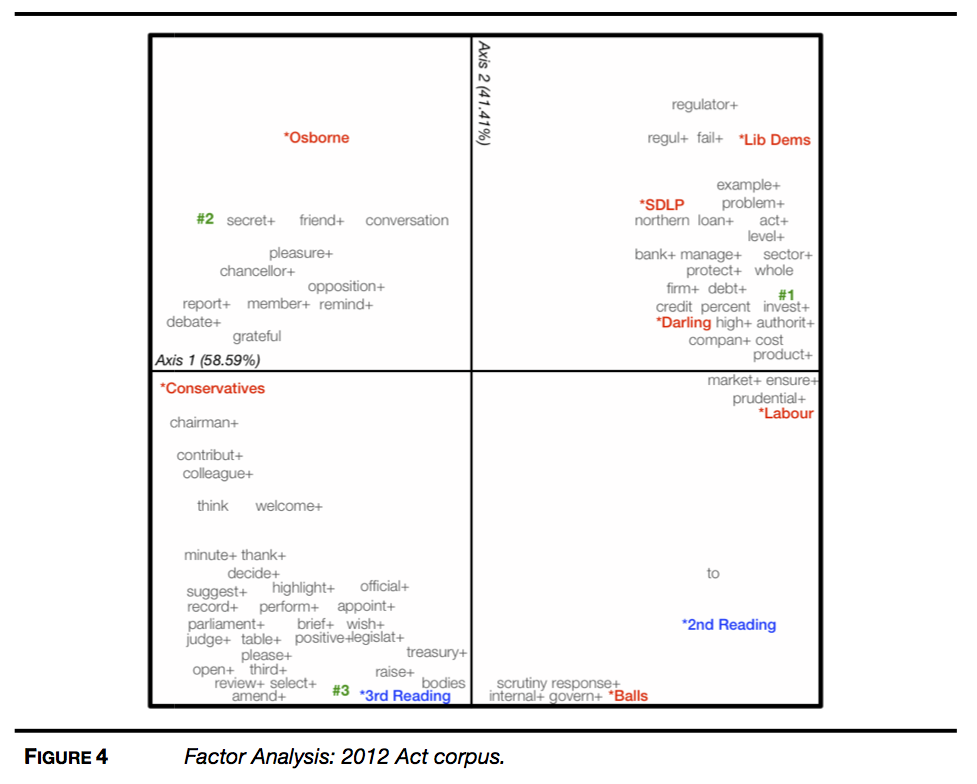

Factor analysis reveals the links between each actor and the classes. Figure 3 represents the 2010 corpus. The analysis accounts for around 72% of the inertia in the corpus; that is, it explains 72% of the association between topics. Likewise, Figure 4 represents the 2012 corpus, but attains a higher association.

In both corpora, Conservative party members dominate the ‘Parliamentary language and rhetoric’ classes, where the Labour and Liberal Democrat parties are most closely associated with the substantive details of the legislation. Of note is the position of the Chancellor (and Shadow Chancellor) in both debates; George Osborne and Alistair Darling occupy similar semantic space (debating the technicalities of the legislation) in the 2010 corpus, but George Osborne and Ed Balls in the second corpus are very distinctly different. Again we see that in the earlier debates, the Conservatives took a stance that was mostly based on evidence (Class #3), later switching to a position of rhetoric (Class #2). The Liberal Democrats remain very distinct from their coalition partner during both corpora, suggesting that there may be a difference of opinion between them. This would certainly be consistent with their manifestos, in which only the Conservatives offer substantive policy suggestions (Conservative Party, 2010; Liberal Democrat Party, 2010). There seems to be a consistent attempt to ‘win the arguments’ against the FSA by the Conservative Party, and this continues throughout the two sets of legislation. However, the evidence shows a stark difference in the substantive content of those arguments. The 2010 corpus exposes predominantly academic arguments, whereas the 2012 corpus shows a shift towards rhetoric. Both are clearly targeted at exposing the inadequacy of the existing framework, but play against the critical junctures thesis.

If the critical junctures theory is correct in positing a cycle of policy failure, paradigm shift and emulation, then it seemingly doesn’t apply in the case of the FSA. If it did apply, we would expect to see consistent, policy-failure-based argument against the FSA, and that this argument be more prevalent in the later corpus, when the Conservatives, as the proponents of the policy, would need to most strongly make their case to gain the support of their coalition partners. Instead, we see simple rhetoric and arguments of political failure. There is no paradigm shift apparent in this latter corpus; and no policy failure to spark it. Instead, we see party politics taking centre stage in the Parliamentary debates.

Conclusion

This paper set out to explore the reasons for the dissolution of the FSA in the Financial Services Act 2012. The results from the content analysis seem to support a hypothesis of partisan politics as the driving force behind this decision, with academic argument giving way to rhetoric and opportunistic ‘point-scoring’. The critical junctures thesis proves insufficient for explaining the proliferation of the 2012 Act. Where the critical junctures thesis relies on policy failure as a necessary condition for paradigm shift, no such policy failure occurs consistently throughout both legislative cases highlighted here. Instead, it is likely the electoral pay-offs play a large part in decision to disband the FSA; it acts as tool to highlight the inadequacy of the previous government’s economic policy. Future research may wish to look at these motivations in more detail.

The implications of these findings may be significant. If parties engage in wide-scale regulatory reform on a regular basis, this has the potential to create uncertainty in markets — something that would act against the long-term interests of economic growth and prosperity. Moreover, if the driver of policy arguments in these areas is not academic, but rhetorical, then there is a risk those optimal institutional arrangements are thrown aside in favour of sub-optimal solutions purely to allow governing parties to ‘make a point’.

Of course, this data set is limited, and a wider view of the debate around these issues may reveal more prominence of arguments suggesting policy failure, but this paper has at least evidenced that this area of policy is one which cannot be purely explained using existing theoretical frameworks, such as the critical junctures thesis.

- Alesina, A. and Tabellini, G. (2005) ‘Why Do Politicians Delegate?’, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. 11531.

- Bailey, A. and Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2008) ‘Does Deliberation Matter in FOMC Monetary Policymaking? The Volcker Revolution of 1979’, Political Analysis, 16(4), 404-427.

- Bailey, A. and Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2010) ‘Deliberation and Oversight in Monetary Policy, 1976-2008’, Southern Economic Association Annual Meeting, Atlanta, 20th-22nd November, 2010.

- BBC (2010) ‘Election causes financial reforms to be dropped’, [online], available: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/8608969.stm [accessed 10 March 2013].

- Boettke, P. J., Coyne, C. J. and Leeson, P. T. (2008) ‘Institutional Stickiness and the New Development Economics’, American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67(2), 331-358.

- Briault, C. (1999) ‘The Rationale for a Single National Financial Services Regulator’, Financial Services Authority Occasional Paper No. 2.

- Chubb, J. E. (1988) ‘Institutions, the Economy, and the Dynamics of State Elections’, The American Political Science Review, 82(1), 133-133.

- Conservative Party. (2010) ‘Invitation to Join the Government of Britain: The Conservative Manifesto 2010’, Conservative Policy Unit.

- Downs, A. (1957) ‘An economic theory of democracy’, New York :: Harper & Row.

- Financial Services Act 2010, (c.28), London: Stationery Office.

- Financial Services Act 2012, (c.21), London: Stationery Office.

- Fiorina, M. P. (1989) ‘Congress: keystone of the Washington establishment’, 2nd ed., London: Yale University Press.

- Gilardi, F. (2010) ‘Who Learns from What in Policy Diffusion Processes?’, American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 650-666.

- Hall, P. A. and Taylor, R. C. R. (1996) ‘Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms’, Political Studies, 44(5), 936-957.

- Joint Committee on Financial Services and Markets (1998) ‘Joint Committee on Financial Services and Markets – First Report’ London: Stationary Office

- King, M. (2005) ‘Epistemic Communities and the Diffusion of Ideas: Central Bank Reform in the United Kingdom’, West European Politics, 28(1), 94-123.

- Kronberger, N. and Wagner, W. (2000) ‘Keywords in Context: Statistical Analysis of Text Features’ in Bauer, M. W. and Gaskell, G., eds., Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook, London: SAGE, 299-317.

- Kydland, F. E. and Prescott, E. C. (1977) ‘Rules Rather than Discretion: The Inconsistency of Optimal Plans’, Journal of Political Economy, 85(3), 473-491.

- Liberal Democrat Party. (2010) ‘Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010’, Liberal Democrat Publications.

- Marcussen, M. (2005) ‘Central banks on the move’, Journal of European Public Policy, 12(5), 903-923.

- Moser, P. (1999) ‘Checks and balances, and the supply of central bank independence’, European Economic Review, 43(8), 1569-1593.

- North, D. C. (1990) ‘Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance, Political economy of institutions and decisions’, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pierson, P. (2000a) ‘Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics’, The American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251-267.

- Pierson, P. (2000b) ‘The Limits of Design: Explaining Institutional Origins and Change’, Governance, 13(4), 475.

- Riker, W. H. (1962) ‘The theory of political coalitions’, New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2005) ‘Measuring Ideas More Effectively: An Analysis of Bush and Kerry’s National Security Speeches’, PS: Political Science & Politics, 38(04), 701-711.

- Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2008) ‘The Congressional Debate on Partial-Birth Abortion: Constitutional Gravitas and Moral Passion’, British Journal of Political Science, 38(03), 383-410.

- Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2010) ‘Problems and solutions in displaying results from Alceste’, [online], available: http://personal.lse.ac.uk/SCHONHAR/ [accessed March 2013].

- Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2012) ‘Looking at Congressional Committee Decisions from Different Perspectives: Is the Added Effort Worth It?’, 5th ESRC Research Methods Festival, St Catherine’s College, Oxford 2nd-5th July 2012, 1-39

- Schonhardt-Bailey, C., Yager, E. and Lahlou, S. (2012) ‘Yes, Ronald Reagan’s Rhetoric Was Unique—But Statistically, How Unique?’, Presidential Studies Quarterly, 42(3), 482-513.

- UK Cabinet Office (2010) ‘The Coalition: Our Programme for Government’, Stationery Office, 9.

- van der Brug, W., van der EijK, C. and Franklin, M. (2007) ‘The Economy and the Vote: Economic Conditions and Elections in Fifteen Countries’, Cambridge University Press.