This dissertation was written as a summative part of my undergraduate studies at the London School of Economics.

In 1997, the Bank of England was granted independence by, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown. The subsequent Act of Parliament gave the newly independent Bank operational control over monetary policy instruments – primarily, the control of the Bank’s base lending interest rate – and an explicit inflation-targeting mandate (Bank of England Act 1998). This target, determined by the Chancellor, was set initially at 2.5% on the Retail Price Index (Brown 2003a) and was later revised to 2.0% on the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (Brown 2003b). The task of meeting this target was delegated to the newly formed Monetary Policy Committee (MPC).

The committee comprises nine members. Four ‘external’ members are directly selected by the Chancellor and five ‘internal’ members – the Governor, two Deputy Governors and two Executive Directors of the Bank – are appointed in consultation with the Crown and Government (Bank of England Act 1998, Bean and Jenkinson 2001 p.434). In effect, the Chancellor has at least some influence in every appointment to the committee (Hix et al. 2010 pp.733-734).

This particular appointment process poses a potential problem. The delegation of monetary policy to central banks has long been argued on the basis of removing political interference and creating macro-economic stability. Governments can use delegation as a ‘credible commitment’ on the economy (Kydland and Prescott 1977, Barro and Gordon 1983, Thatcher and Sweet 2002). But, if the Chancellor has an apparently significant influence over the appointment process of MPC members, does the spectre of political control and thus, a credibility crisis, still exist?

Does de jure control of the appointment process also mean de facto control of the policy outputs of the MPC? That is, does the Chancellor have the ability to manipulate the Bank’s base interest rate decisions, or any other monetary policy instrument decision, by virtue of whom he appoints?

The answer to these questions lies in resolving a debate at the heart of political science; are actors’ preferences stable and, therefore, can their actions be reliably predicted? If preferences are stable and actions are predictable, then the level of control given to political actors over the appointment process is something that should be given careful attention, as the very idea of a credible commitment may be misguided. This is particularly true in instances where one individual – such as the Chancellor of the Exchequer – controls the appointment process.

Using the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee as a case study, I explore the significance of the appointment process to policy outputs, by establishing whether or not preferences are stable or change over time. I begin by exploring the academic literature on central bank independence, decision-making, preference formation and change and expose an obvious contradiction in the literature that is yet to be fully explored in the context of monetary policy committees. With this theoretical background in place, I move on to establish my hypothesis – that preferences change – and discuss how this might be observed empirically. Next, I lay out my methodology of automated content analysis, how this has been applied to the case study and my findings.

In applying this methodology, I find evidence both of preference change and preference stability, but move beyond the one-dimensional ‘hawk-dove’ dimension highlighted in existing literature to expose a more intricate background to the preference formation process of MPC members. I conclude that the type of appointment process used for monetary policy committees does matter, but that the extent to which it is able to actually affect policy outputs is uncertain, because the preferences of members change and their actions cannot be reliably predicted, particularly during times of economic shocks.

Reviewing prior research

Why do we delegate to independent central banks?

Delegation arises from a ‘time consistency problem’ (Kydland and Prescott 1977, Moser 1999). Politicians have incentives – arising from ‘electoral’ and ‘partisan’ politics (McNamara 2002) – to use macro-economic policy instruments, such as interest rates, or government fiscal expenditure, for their own short-term advantage, even at long-term cost to themselves and others (Kydland and Prescott 1977, Moser 1999). Political actors will use interest rates and fiscal policy, particularly close to elections, to create positive public perceptions of their economic performance through, for example, pursuing artificial economic ‘booms’, or create surprise inflation to reduce unemployment. Despite the fact that these policies create economic uncertainty and instability, parties continue to pursue them because the electoral incentives are significant – a wealth of research suggests a positive correlation between strong economic performance and electoral outcomes (Chubb 1988, van der Brug et al. 2007).

The end result of this ‘political business cycle’ (Nordhaus 1975) is a ‘credibility crisis’ where politicians cannot be trusted to pursue policies that create sustainable growth (Kydland and Prescott 1977, Barro and Gordon 1983, Thatcher and Sweet 2002). The solution to this crisis is to remove these macro-economic policy instruments from political control entirely, delegating them to independent institutions, such as central banks (Kydland and Prescott 1977, Barro and Gordon 1983). In the case of price stability, delegation of monetary policy to an independent central bank and giving it a clear inflation-targeting mandate is seen as an effective institutional arrangement for resolving the credibility problem (Rogoff 1985).

The corner stone of the trust inherent in this delegation rests on the implied behaviour of central bankers. The theory views central bankers as economically conservative; they are believed to be less prone to accept high levels of inflation and, with the absence of an electoral cycle and representative pressures, they are less likely to take risky decisions due to their long-term time-horizons (Rogoff 1985, Marcussen 2005).

This act of delegation is why the question of who controls the appointment process is important. If politicians need to be removed from monetary policy decisions in order to create long-term economic stability, do certain appointment processes actually keep them very much involved in the decisions that are meant to be locked away? As previously mentioned, the answer to this lies in the study of preference change.

How and why do we measure preferences in political science?

The concept of preferences is an important consideration for political science; understanding the preferences of policymakers enables us to know more than just the what of the policymaking process, but also the how and the why (Bailey and Schonhardt-Bailey 2013 (forthcoming) p.1). But, like many political science phenomena, observation of preferences is empirically difficult and prior research has had to rely on real world cases as a proxy in order to infer the motivations of actors.

Research into the preferences of central bankers has tended to focus on the so-called ‘hawk-dove dimension’ – a uni-dimensional policy space, along which members might be located as a ‘hawk’ or a ‘dove’ (Chang 2003, Sibert 2003, Hix et al. 2010). A dove may be considered as more willing to accept higher rates of inflation, opting for lower interest rates, whilst a hawk can be conceptualised as more inflation averse, opting to promote higher interest rates, in identical economic circumstances (Hix et al. 2010 p.732).

Much of the literature relies on voting records and a variety of quantitative methods as a proxy for preferences. Others have used qualitative data – such as minutes, transcripts, or speeches – and various quantitative and qualitative methods to try and understand the causes of policy. The merits of each approach are contested, but one consistent baseline can be seen – it is important to use an appropriate proxy to assess preferences in political science.

On the use of qualitative data, scholars have attempted to brush off its importance, implying that there’s nothing to be gleaned from it because actors aren’t truthful, or that analysis of text doesn’t tell us anything useful. Scholars such as Meade (2005) and Bailey & Schonhardt-Bailey (2013 (forthcoming)) challenge these arguments. They argue that quantitative data have limitations of their own that can only be met by using qualitative data sources. Whilst voting records are useful for describing the end results of the political process, they can’t explain the motivations of actors as they over-simplify the processes of preference formation and decision-making (Meade 2005 p.94, Bailey and Schonhardt-Bailey 2008 p.408-409, 2013 (forthcoming) p.5). Moreover, researchers that rely exclusively on quantitative data, such as voting records, run the risk of ‘retro-fitting’ (Bailey and Schonhardt-Bailey 2008 p.408-409, 2013 (forthcoming) p.113). Observing an ideational trend after-the-fact and that it occurs at the same time as a change in policy outputs doesn’t necessarily mean that this trend was a motivation in the decision-making process for those actors (Bailey and Schonhardt-Bailey 2008, 2013 (forthcoming)); correlation and causation are not one and the same. In order for us to understand the motivations of actors, we must seek data that shows, explicitly, what actors were thinking, saying and doing throughout the decision-making process – not merely the end result. In the absence of research techniques that actually allow us to read people’s minds, the closest proxy researchers have available to do this is to use what people say or write. But how is this important in the context of the appointment process?

In 2010, Hix, Høyland & Vivyan published a paper on the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee. They used voting records from MPC meetings to infer the position of committee members along the previously mentioned hawk-dove dimension (Hix et al. 2010 pp.740-745). In the subsequent discussion, they argue that there may be a link between the relative average position of the committee on the hawk-dove spectrum and the government’s fiscal spending plans, such that the Chancellor of the Exchequer chooses relative hawks during a period of fiscal expansion and relative doves during periods of fiscal restraint in order to maintain price stability whilst meeting his economic objectives (Hix et al. 2010 pp.745-753). Whilst they do not offer firm conclusions on this posited relationship, (Hix et al. 2010 pp.745-753), if this relationship holds and the Chancellor was using his power to manipulate the MPC’s policy outputs, then the supposed resolution to the Labour Party’s economic credibility problem (King 2005) never truly occurred. Indeed, it remains unresolved as the appointment process is still the same today.

Two questions emerge:

- Firstly, does it matter if the Chancellor has the ability to control the committee’s policy outputs based on the members he appoints? If he is simply ensuring that the MPC acts as an economic counter-weight to his fiscal policy; should this be an area of concern?

- Secondly, and more importantly, does this relationship actually hold? A wealth of literature suggests that it may not.

Hix et al.’s model is based on an implicit rational choice theory assumption, in the vein of Tsebelis (1990), Shepsle (2010) and others. They claim they are unconcerned with how an individual member’s preferences are formed, but that “it is sufficient for [them] to assume that MPC members [have] reasonably stable underlying monetary policy preferences, such that a member with more hawkish policy preferences will tend to prefer more restrictive interest rates relative to others,” (Hix et al. 2010 p.738). If this assumption is correct, then their posited relationship between appointments, preferences and policy outputs is likely to hold; the question of who controls the appointment process then becomes a real area of concern that must be addressed in order to establish (or re-establish) the credible commitment to independent institutions. If, however, preferences are not stable and the assumption is incorrect, then the observed relationship becomes less significant. Instead different questions arise about the level of oversight and control necessary in independent institutions. This leads us to the question; are preferences stable over time?

Are preferences “reasonably stable” over time?

The stable preferences assumption sits uncomfortably with findings made in other areas; not only the literature explicitly focussing on monetary policy committees, but also, more broadly, on public policy decision-making and preference formation.

Research on decision-making leads us to a view that the stable preferences assumption might not hold in all cases. Rational choice theory relies on several normative assumptions; that preferences cannot be contradictory, that they are transitive, that actors attempt to maximise their utility, and that actors consistently act in their own self-interest (Tsebelis 1990 pp.24-31). Others, in assessing the theory, have argued actors have access to perfect information and that they are able to see the full repercussions of their actions in a panoramic sense (Simon 1957 p.79). To assess the real world application of rational choice theory, we might consider the case of ‘administrative man’ and ‘economic man’ popularised by Simon (1997, 1957), and later work on ‘bounded rationality’ (Jones 2003). This literature challenges the notion of ‘perfect rationality’ arguing that actors are not omniscient calculators as some rational choice theories assume (Jones 2003 pp.397-398) and that our ‘Incompleteness of Knowledge’ (Simon 1957 p.79) – especially relevant in economic policy, where data are nearly always incomplete, based on estimates and uncertain – means that we must make decisions within certain limits. Rational choice assumptions may not be the best way to think about our preference forming and decision-making behaviour.

Others have furthered these concepts, arguing decision-making is a process of ‘muddling through’ (Lindblom 1959 pp.80-81). Actors tend to make policy incrementally rather than on a wholesale basis – making decisions about the ‘branches’, not the ‘roots’ (Lindblom 1959). This is true in many areas of public policy, where actors engage in ‘successive limited comparison’ and ‘mutual adjustment’ (Lindblom 1959 pp.81-88) altering government projects and budgets at the margin, not the base (Wildavsky 1964). These theories imply some – though not absolute – preference stability but also that final decisions may not necessarily match an actors’ prior preferences (‘priors’). These works open the door for some theoretical basis of preference change and emphasise the need to look beyond voting data alone, as votes may not be reflective of preferences.

The ‘critical junctures’ thesis from the historical institutionalism literature gives us one further example of how preferences might change. At a time of large and unexpected events, preferences may begin to change when existing policy fails to accommodate or correct a political or economic shock (Hall and Taylor 1996, Baumgartner and Jones 2002, Marcussen 2005). Policy failure provides opportunities for policy entrepreneurs (Marcussen 2005) and epistemic communities (King 2005) to step in and engineer ‘paradigm shifts’ by changing the policy preferences of actors (King 2005). This literature makes it plausible that events such as the global financial crisis, a recession or a crash such as the burst of the dot-com bubble might have the effect of changing policymakers’ views of the world and, by implication, their preferences.

Broad theoretical literature on decision-making and preference formation clearly shows a contestation between a stable and a changeable view of preferences. The literature on central banking policy committees makes this case clearer.

Delegation to committees or individuals?

Many central banks use committees, rather than individuals, as their monetary policy decision-making body (Lombardelli et al. 2005 p.182). Given the increasing evidence suggesting committees produce comparatively higher quality policy outputs, this isn’t surprising. Research suggests committees are less volatile and less prone to extreme swings than individuals (Blinder and Morgan 2005 pp.800-801) and improve their decisions through pooling of knowledge and shared heuristics (Lombardelli et al. 2005 pp.190-202). At the same time, they are no more inertial when compared to individuals (Blinder and Morgan 2005 pp.797-800).

The literature attributes this to methods of group learning; an environment where members learn from one another and change their views of the world – and perhaps actions – as a result. This ‘opinion updating’ can work in two ways; members might moderate and change their opinions through exposure to new ideas or they might reinforce their ideas through rejecting other members’ views (Barabas 2004 pp.688-689). Importantly, though perhaps obviously, those with long-standing or extreme views are most likely to reinforce their views, where those with less extreme or newer preferences are more likely to change them (Barabas 2004 pp.689-699).

The effect of strong personalities

Researchers have also suggested the composition of the committee itself is important. Bailey & Schonhardt-Bailey (2008, 2013 (forthcoming)) consider the effect of strong personalities on monetary policy committees and their effects on policy outputs. They highlight the case of the ‘Volcker Revolution’ in the 1980s, where the US Federal Open Markets Committee re-oriented its policy to a new focus on inflation targeting. They find that Chairman Volcker had a significant impact on this re-orientation (Bailey and Schonhardt-Bailey 2008, 2013 (forthcoming)). Their case shows that dominant personalities can have a significant impact on the preferences of other committee members. Notably, their research is based on content analysis, rather than quantitative data sources, highlighting the usefulness of qualitative data to assess preference change.

The literature on preference formation clearly conflicts over the concept of stable preferences. As previously mentioned, this must be resolved if we are to understand how significant the appointment process is in the context of the MPC and its policy decisions. The following sections lay out a methodology to test this question and assess if the appointment process is a concern or whether its significance has been overstated.

Hypothesis formulation

Much of the literature leads us to an argument that preferences are able to change and are anything but “reasonably stable” (Hix et al. 2010 p.738). The case study considered in this paper — the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee — relies on a committee structure in order to take its decisions (Bank of England Act 1998, Bean and Jenkinson 2001 pp.437-438), and indeed, the committee’s decision-making process is one that encourages debate by virtue of its decision-making process. Consensus decision-making is not required, and members are free to vote against the majority provided they can give a justification for their decision (Bean and Jenkinson 2001). Given this context, I reach the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The underlying monetary policy preferences of members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee change over time.

The literature highlights preference change as a process of individuals choosing to accept or reject arguments they encounter, and then aggregating those arguments in order to form a preference – be that a reinforced preference, or a new view of the world (Barabas 2004). As in prior research, I conceptualise members’ preferences as traceable to a policy space, but this needn’t necessarily be a uni-dimensional space such as the hawk-dove dimension. Instead, I view positions in a policy space as simplified end-points in the preference formation process (Barabas 2004). These end-points are seen as a composite of variables and external effects, such as the composition of the committee, its membership, the existence and significance of dominant personalities, each members’ prior view of how the economy ‘works’ and so on. The different weights given to each of these ‘underlying preferences’ and variables, in each member’s preference-forming calculations, come together to create those end-points. This concept of preference formation allows us to test preference change as we can observe the quantity and the substantive content of each variable.

I predict three different ways in which we might observe preference change; logical contradiction, development, and/or stability.

Logical contradiction: a preference change seen as a reversal of a members’ policy position – i.e. they change their minds.

In the case of logical contradictions, we might observe hawks becoming more dove-like, or vice versa. But it isn’t enough, for example, that members vote for interest rate increases in one period, and cuts in the next; this would ignore the context of their votes and their preference formation. Instead, there should be evidence that members have changed how they form their preferences in a way that directly contradicts their priors. Members might suggest initially that certain policies are ineffective at tackling certain phenomena and later suggest the same policy is essential; this would be evidence of a logical contradiction.

Development: a preference change as an advancement of a view – i.e. members go from being slightly-hawkish to extreme-hawks.

Again, preference development isn’t simply a case of voting for small rate increases in one time-period, and larger rate increases in the next, or vice versa. There should be evidence that members’ views have developed in some way, such that they now hold their beliefs more strongly than before. Members might argue a policy instrument is partially helpful in a certain case and then essential in a similar case at a later date.

Stability: preferences as reinforced and static over time – i.e. hawks remain just as hawkish as before.

In the case of stability, it is again insufficient to simply see continuous voting for the same policy. There should be evidence of a calculation within which the components stay the same. A member might continuously suggest a certain policy is the most effective way of tackling a specific phenomenon, for example.

Evidence of preference stability would be concerning in the context of the issue raised in this paper; it would suggest that, given the right kinds of information prior to appointment, the appointments process could be used as a political tool, and that the Bank of England is neither ‘behaviourally’ nor ‘operationally’ as independent as we might think (Cukierman et al. 1992). Stable preferences imply predictable behaviour and thus if the Chancellor picks the right people, he can predict the actions of the committee and construct it to his advantage. Evidence of either logical contradictions, or preference development, would start to question the real significance of the appointment process in this context.

With this conceptual framework in place, the following section explains in detail the methodology used to explore the hypothesis.

Methodology

It should be clear from the preceding discussion that simply creating a statistical model and using voting data and regression analysis would be an ineffective methodology for assessing my hypothesis; raw statistics do not allow us to investigate the broad motivations of actors, nor do they provide us with enough granular insight.

Prior research has used content analysis of qualitative data such as transcripts and minutes of meetings to investigate preference change. Unlike in the case of other central banks however, the Bank of England does not publish transcripts of MPC meetings and the minutes of those meetings tend not to be attributable to individuals, making them useful for analysis of the committee at the aggregate level but not for this case study. The Bank does, however, publish speeches and articles by members when they act in their capacity as representatives of the Bank. Whilst these are not an exact substitute for transcripts – meaning that variables such as the effect of the committee process are not explicitly observable – these speeches are attributable to individuals and they still provide a time-related aspect, like transcripts.

I employ full-text, automated, content analysis of these speeches and articles – using the ‘Alceste’ software package – to draw out the development of members’ preferences over time. This approach has previously been described as a complete methodology through its integration of “a multitude of highly sophisticated statistical methods” (Kronberger and Wagner 2000 p.306) and has been extensively detailed elsewhere (Bailey and Schonhardt-Bailey 2008, 2010, 2013 (forthcoming), Schonhardt-Bailey 2005, 2008, 2010, 2012, Schonhardt-Bailey et al. 2012). A brief summary of how Alceste is used is detailed below.

The Alceste methodology

The researcher selects a series of initial sampling units, which can be understood as cases. These ‘Initial Contextual Units’ (ICUs) are then compiled into one or more corpora and prepared for analysis by removing or substituting any data that may interrupt or distort the analysis. Each ICU is ‘tagged’ with ‘passive variables’, such as the name of the author/speaker, the date and so on, such that the ‘tags’ are representative of the case and the characteristics the researcher wants to draw out.

The software breaks each ICU into smaller working units – ‘Elementary Contextual Units’ (ECUs) – based on the structure of sentences, word length and punctuation. Using a recursive algorithm, Alceste assesses co-occurrences, classifying each word form and ECU, and assigning a Chi-squared value representing the significance and distinctiveness of those forms from those in the rest of the text. The resulting output is a hierarchical classification, in which each theme or topic (‘class’) is as statistically unique as possible (Bailey and Schonhardt-Bailey 2010 pp.28-48).

Each ICU in this paper represents an individual speech or article made by individuals on the MPC. The data can be obtained from the Bank of England’s website. ICUs were collected from the majority of members between 1997 (the committee’s inception) and December 2012. The members used in the analysis were selected based on several criteria.

First, individual members must have served at least two years on the MPC. Members serving less than two years, or for which no data were available, were excluded. This was to ensure a time-related element to the analysis. In addition, I wanted to ensure that the dataset was not unnecessarily biased towards discussion of the financial crisis, as much of that discussion is likely to be less relevant to the concept of ‘underlying monetary policy preferences’. To do this, I needed to exclude those presently on the committee. This had to be balanced against a further consideration however; excluding all current members would have meant losing those members that prior research had indicated could be most revealing – such as the Chair (Bailey and Schonhardt-Bailey 2008, 2013 (forthcoming)). To ensure there was a balance between these two considerations, two further criteria were applied. Members assessed must have either (a) left the committee, having finished their term, or (b) been on the committee for at least two full terms if they are still serving members. These criteria helped to balance the aforementioned trade off and were intended to maintain the robustness of the dataset. Details of members included or excluded, given the above criteria, are shown in Appendix 1.

| Hawks | Centrists | Doves |

|---|---|---|

| Andrew Sentance | Marian Bell | Sushil Wadhwani |

| Andrew Large | Stephen Nickell | David Blanchflower |

| Tim Besley | Ian Plenderleith | DeAnne Julius |

| Charles Bean | Christopher Allsopp | |

| Kate Barker | Adam Posen | |

| Edward George | ||

| David Clementi | ||

| Rachel Lomax | ||

| John Gieve | ||

| Charles Goodhart | ||

| Williem Buiter | ||

| Paul Tucker | ||

| Mervyn King | ||

| John Vickers |

The literature suggests that different members of a committee will be more or less likely to update their preferences based on whether their priors are moderate or extreme (Barabas 2004). My methodology exploits this conclusion, dividing members along a single dimension for the purposes of selecting individuals for in-depth analysis. Using the results from Hix et al. (2010), three corpora were compiled representing the ‘hawks’, the ‘doves’ and the ‘centrists’. My hypothesis is not, however, concerned with aggregate preferences, but individuals. Hence, I use the results of these initial corpora to find the most statistically significant members. The significance of members, (or indeed any part of the results) is given by the Chi-squared value, with one degree of freedom, of the passive variables. The critical values are shown in Table 2.

| Statistical significance | Chi value |

|---|---|

| Not significant | 2.71 or lower |

| 10% | 3.84 or lower |

| 5% (*) | 6.63 or lower |

| 1% (**) | 10.80 or lower |

| Less than 1% (***) | 10.80 or higher |

Larger Chi-squared values represent higher statistical significance, and greater association of the variable. However, these values can only serve to give us an ordinal ranking of the significance of each variable, rather than a relative significance, (i.e. a Chi-squared value of 20 is more significant than a value of 10, but not twice as significant). I test the most significant member from each class in their own corpus and assess the results against the three hypothesized observations in the previous section (logical contradiction, development and stability).

Due to the fact that some MPC members hold more than one role within the Bank of England (such as the Governor), they are likely to focus on areas not specifically relevant to their work on the MPC in their speeches and articles – an example might be discourse regarding regulation of the banking system. Because of this, not all classes are included for the purposes of selecting members for in-depth assessment. Classes (and thus, members) are excluded from selection if the results show that word forms relating to monetary policy (‘inflation’, ‘monetary’, ‘policy’, ‘price’, ‘level’, etc.) are absent from a class and that absence is statistically significant.

The following sections detail my results and a discussion of my findings, along with the practical implementation of my methodology.

Results and discussion

More than 1.6 million words and 615 ICUs were assessed to obtain the initial classifications and select members for in-depth analysis. Table 3 shows the basic statistics.

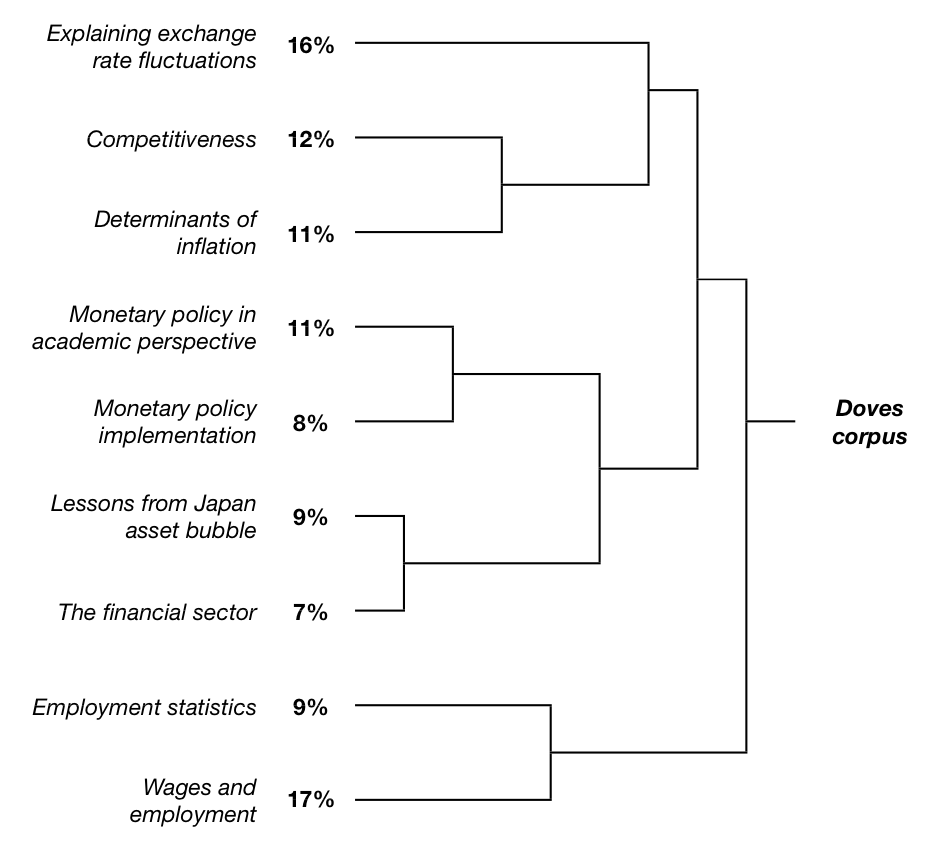

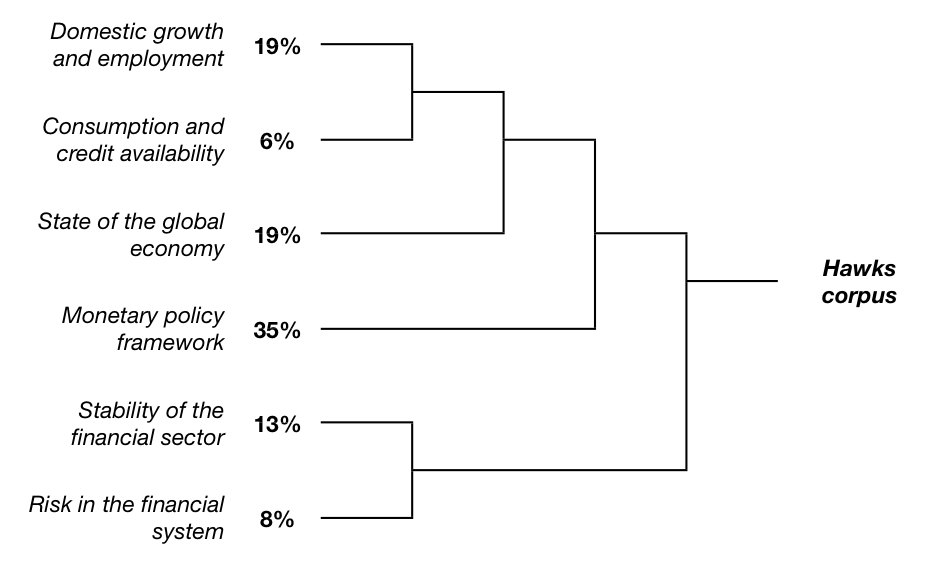

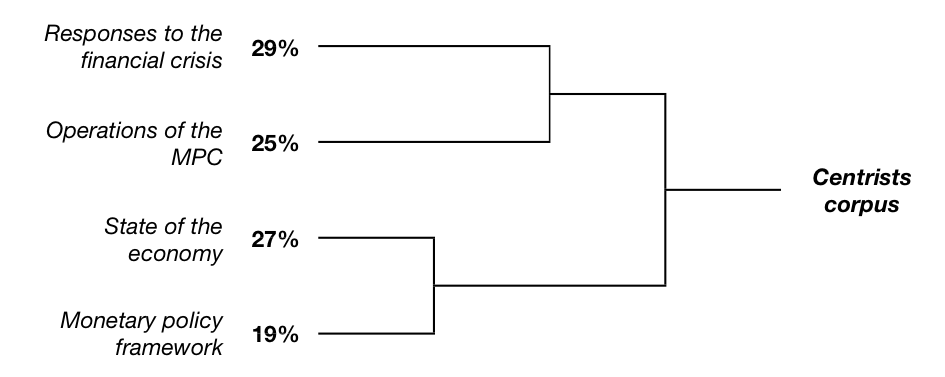

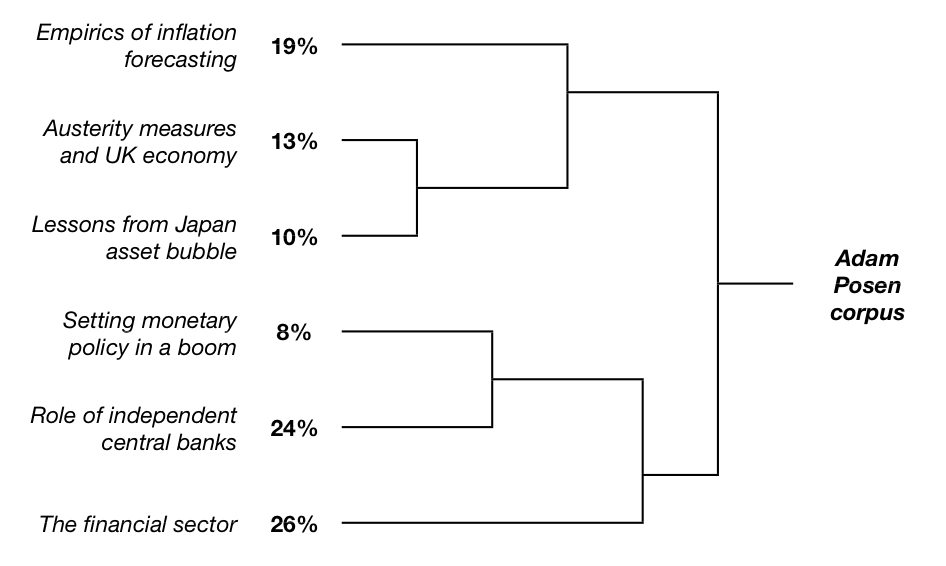

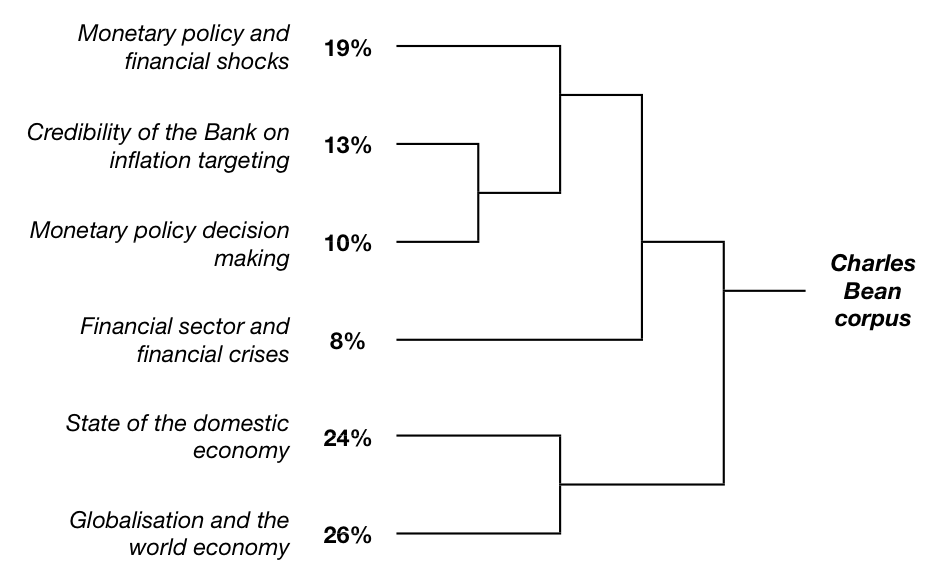

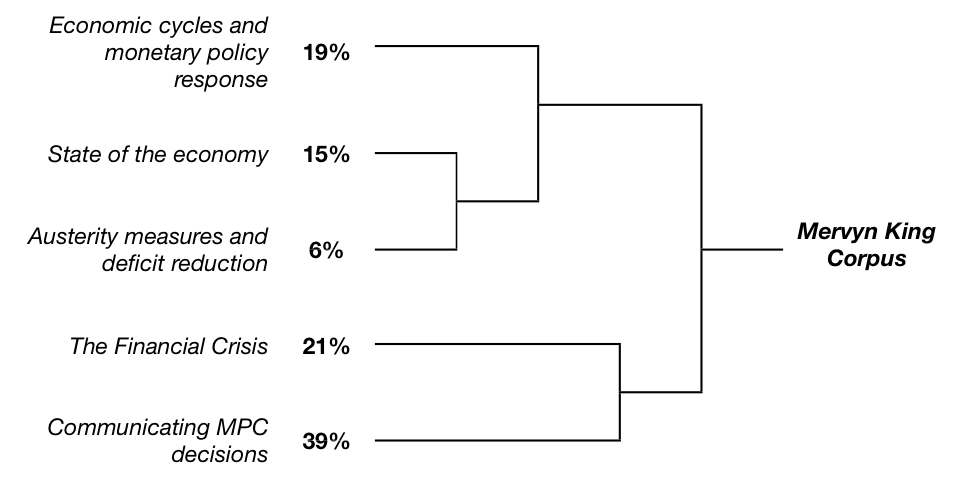

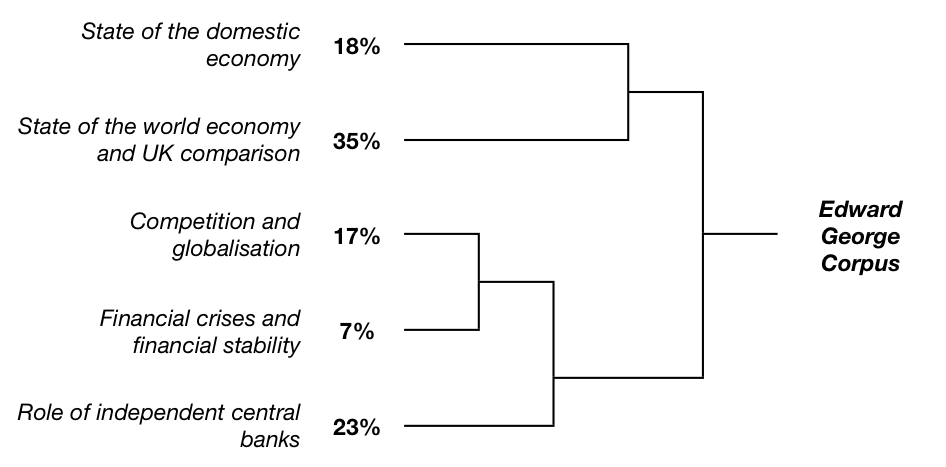

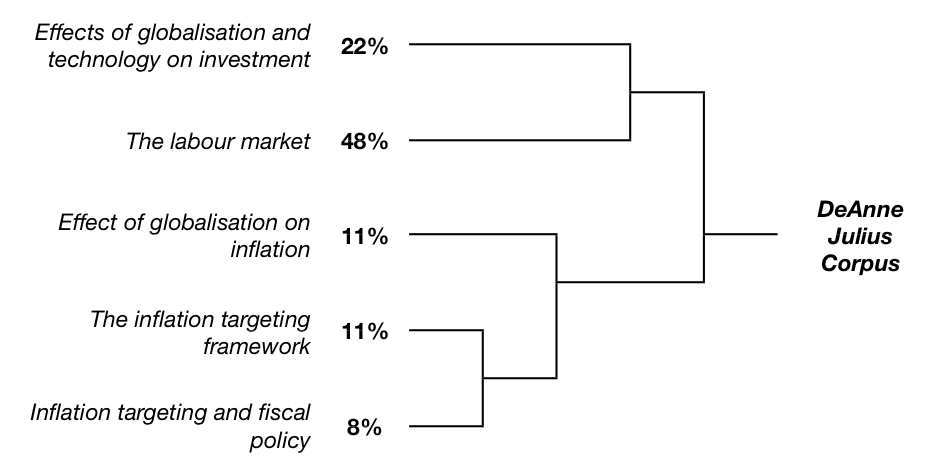

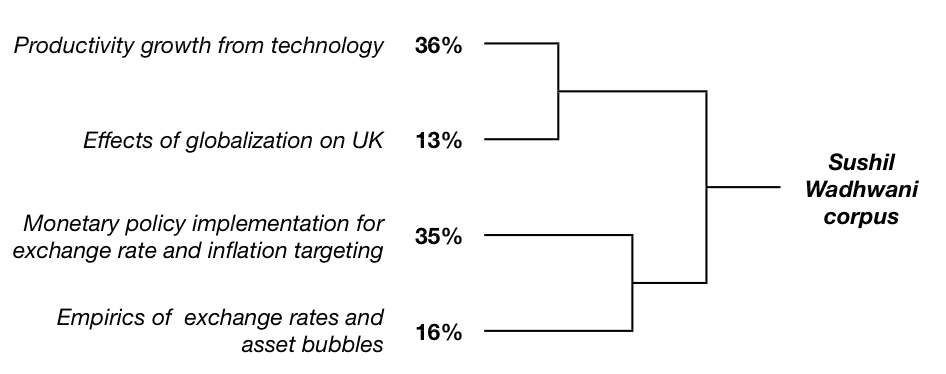

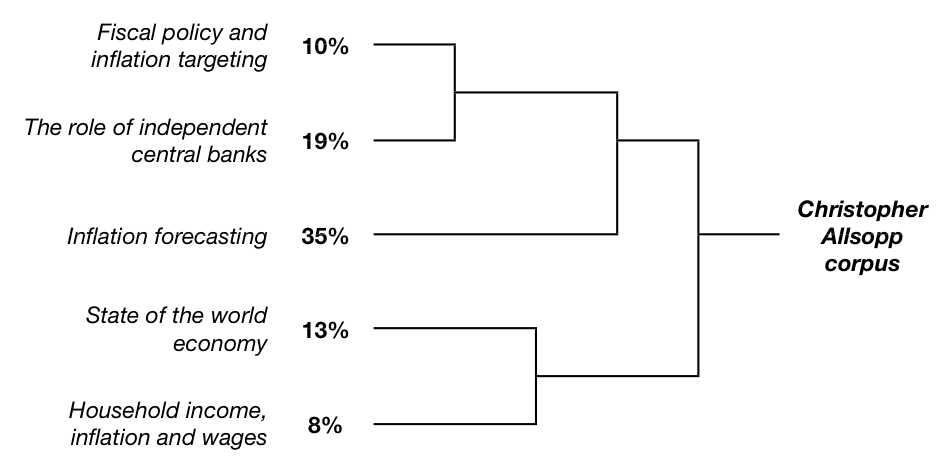

Figures 1, 2 and 3 show the descendant hierarchical classifications for each of the initial corpora. The descendant classifications show the relationships between classes and the distribution of the discussion. Each class has also been labelled based on an assessment of the significant word forms and ECUs for each class (these are not provided by Alceste, but assigned by the researcher).

| Hawks | Centrists | Doves | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total word count | 177,710 | 1,151,559 | 297,811 |

| Unique words analysed | 7,650 | 24,675 | 14,177 |

| Passive variables (tagged indicators) | 27 | 50 | 33 |

| Initial Contextual Units (ICUs) | 44 | 320 | 51 |

| Classified Elementary Contextual Units (ECUs) | 3,178 (82%) | 7,691 (74%) | 5,237 (77%) |

| Number of lexical classes | 6 | 4 | 9 |

The most striking result from these corpora is that despite the centrists corpus being significantly larger than the others, this corpus contains the least number of lexical classes; only four in total, compared with six in the hawks and nine in the doves. This shows the discourse among the centrists is more focussed than that of the other groups. The large number of classes in the doves corpus is perhaps expected, given these members have different specialisms and come from a range of different backgrounds; for example, DeAnne Julius comes from industry, whilst Sushil Wadhwani comes from a financial background.

Further assessment of the classes reveals that, as predicted, some of the discourse within speeches isn’t necessarily relevant to the work of the MPC, but rather to the functions of the Bank of England in general. The table in Appendix 4 shows the classes for each corpus, the most closely associated member for each class (i.e. the member whose passive variable is highest ranked), their ranking and Chi-squared value, the most representative word forms for the class (with ranking and Chi-squared value), and the most significantly absent word forms for the class (also with Chi-squared value and ranking). This data clearly shows that not all classes relate to ‘underlying monetary policy preferences’ as I conceive them and the justification for narrowing the data as previously outlined appears justified.

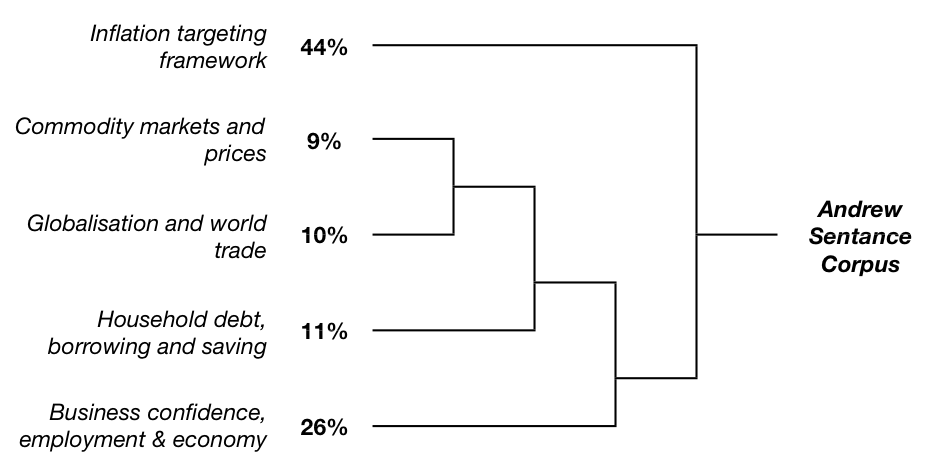

After the process of narrowing the data was completed, eight members remained for assessment; Andrew Sentance (hawk), Mervyn King, Edward George, Charles Bean (centrists), Sushil Wadhwani, Adam Posen, Christopher Allsopp, and DeAnne Julius (doves). The basic results are shown in Table 4, and relevant descendant hierarchical classifications are shown on the following pages. All members attain a robust rate of ECU classification.

| Total words | Unique words | Passive variables | ICUs | Classified ECUs | Lexical Classes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentance | 120,048 | 5,386 | 21 | 27 | 2,205 (82%) | 5 |

| King | 260,243 | 12,096 | 33 | 74 | 6,431 (88%) | 5 |

| George | 163,535 | 7,434 | 22 | 64 | 3,912 (82%) | 5 |

| Bean | 155,759 | 9,037 | 28 | 35 | 2,976 (73%) | 6 |

| Wadhwani | 76,761 | 6,232 | 17 | 14 | 1,456 (79%) | 4 |

| Posen | 80,209 | 7,084 | 19 | 16 | 1,476 (79%) | 6 |

| Allsopp | 18,897 | 2,704 | 7 | 2 | 324 (86%) | 5 |

| Julius | 21,064 | 3,194 | 10 | 5 | 384 (67%) | 5 |

In order to explore the hypothesis, I return to the expectations established earlier. By qualitatively assessing the ECUs of each member, and using Alceste’s factor analysis and cross-data analysis functions, I find examples of logical contraditions, preference development and preference stability.

Logical contradictions

A logical contradiction can be understood as a reversal of a member’s position. Several members show evidence of this type of change.

Andrew Sentance is perhaps the most striking case. In 2008, Sentance appears particularly concerned with the “downside risks” to economic activity and inflation, presenting this view consistently throughout this period. Some representative ECUs include:

“[…] I am particularly concerned about the downside risks to economic activity created by the current financial turmoil and its impact on economic activity, globally and domestically.”

Data 1: Sentance, Oct 2008. ECU: 1,020. Chi-squared: 12.

“That shifts the focus for policy action more clearly onto the downside risks for inflation from a prolonged period of weak economic activity. […]”

Data 2: Sentance, Oct 2008. ECU: 1,034. Chi-squared: 11.

Sentance clearly believes the financial crisis creates downward pressures on growth and inflation – his preferences could be interpreted as ensuring the MPC focuses on ensuring those downside risks don’t become realities.

Cross-data analysis reveals a change in this view over time. 2010 and 2011 show Sentance rejecting a so-called “pre-occupation” with downside risks:

“[…] the UK economy grew by over 4 percent , which is still the strongest rate of GDP growth we have seen in any calendar year since the late 1980s. ([…] There is a risk that we are making the same mistake again because of the preoccupation with downside risks following the financial crisis.)”

Data 3: Sentance, Nov 2010. ECU: 2,185. Chi-squared: 11.

“[…] too much faith is being put on the impact of a large ‘output gap’ pushing down on inflation and not enough weight has been put on the upward pressure from the global environment and the exchange rate.”

Data 4: Sentance, Feb 2011. ECU: 2,344. Chi-squared: 21.

A focus on downside risks shifts to concerns of upside pressures on inflation. This is clear evidence of a logical contradiction. Sentance has accepted two opposing arguments and used them to form a preference on the need for policy action; moreover he has rejected the former preference in order to create the latter.

These changes are found in ECUs with a high Chi-squared value and thus this espoused contradiction can be interpreted as significant. If we consider the change in context, it becomes even more significant. At the time of these statements, inflation was significantly above target (4.5%, 3.3% and 4.4%) (Bank of England 2011) and growth at the beginning and end of the period was below 0% (OECD 2012, World Bank 2013). In these crude terms, little had changed for the UK’s economic outlook, but this member is arguing for a completely different strategy to ensure price stability. Indeed they voted for a different strategy – voting to cut interest rates throughout the period 2008-2009, and favouring increases thereafter. Already, we see evidence that members’ actions are not as predictable as we might think, and that the appointment process might not feed through to the final policy decisions of members.

Adam Posen is another case; his preference change concerns his views on the real effect of monetary policy on the broader economy. In 2009, he broadly endorses the notion of the ‘neutrality of money’ (Hayek and Klausinger 2012 p.110) – that, over the economic cycle, monetary policy has no real effect on growth or employment – and that the MPC could do very little to prevent financial crises.

“[…] monetary policy really cannot do anything about bubbles. […]”

Data 5: Posen, Dec 2009.

“There is no dependable relationship between central bank’s instrument interest rates, real or nominal, with either housing price growth or equity market appreciation […]”

Data 6: Posen, Dec 2009.

“[…] central banks do not control broad money growth – they only control short-term interest rates and (at best) narrow money growth. […]”

Data 7: Posen, Dec 2009.

Posen’s argument is based on empirics; the MPC cannot do more, he argues, because they do not have the necessary policy instruments.

In 2010, this position appears to soften, with Posen arguing the MPC can and should “do more” to improve growth prospects for the economy. Posen is making the case for policy activism, arguing central bank independence should be about taking action, not ‘keeping up appearances’ of independence:

“Getting unduly caught up in protecting the appearance of central bank independence is doubly mistaken: first, it will not do any good because it is not that appearance which delivers desirable results; […]”

Data 8: Posen, June 2010.

“The case for doing more is about activism for sustaining a period of recovery from a low point, thereby preventing us from getting stuck in a long-term trap.”

Data 9: Posen, Sept 2010.

Interestingly, Posen’s voting record on the base rate doesn’t reveal this preference change – he votes to maintain the interest rate at 0.25% in every meeting. There is evidence of change in the records relating to the Bank’s Quantitative Easing (QE) programme. Posen voted to increase the amount of QE in most meetings from 2010 onwards, but only once prior to 2010; this is likely his way of “doing more” with monetary policy, and clearly there is a change both in preference, and in action. Posen is further evidence that members’ actions cannot be predicted due to changing preferences and more evidence is seen against the importance of appointment processes.

Charles Bean exhibits further evidence of preference change. In 2003 he argues that inflation targeting is a sufficient framework for preventing asset price bubbles and imbalances:

“Are there grounds for thinking the objective is overly focussed on inflation? My own view is no. […]”

Data 10: Bean, Mar 2003.

“So the answer to the question posed in the title is: yes, ‘flexible’ inflation targets are enough. […]”

Data 11: Bean, Mar 2003.

That a member believes the MPC’s mandate is appropriately focussed on inflation is unsurprising, but Bean clearly believes inflation-targeting alone is sufficient to tackle any economic phenomena. By implication, he believes the MPC’s policy instruments are sufficient. Of course, this is in the context of one of the longest periods of growth on record for the UK. Preference change comes in the wake of the financial crisis:

“[…] In my view, […] a modest increase in the official interest rate is unlikely to do much to restrain a credit-asset-price boom that is in full swing.”

Data 12: Bean, Nov 2008.

Where previously, Bean felt the policy framework in place was sufficient to ensure growth and price stability, he now seems to more explicitly recognise the limits of monetary policy. Again, all of these ECUs are significant at the 1% level and are strongly representative of the discourse in these periods.

| Association | Cumulative | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Axis 1 (left to right) |

Real economy vs use of monetary policy |

28% | 28% |

| Axis 2 (top to bottom) |

Financial stability vs inflation targetting |

25% | 53% |

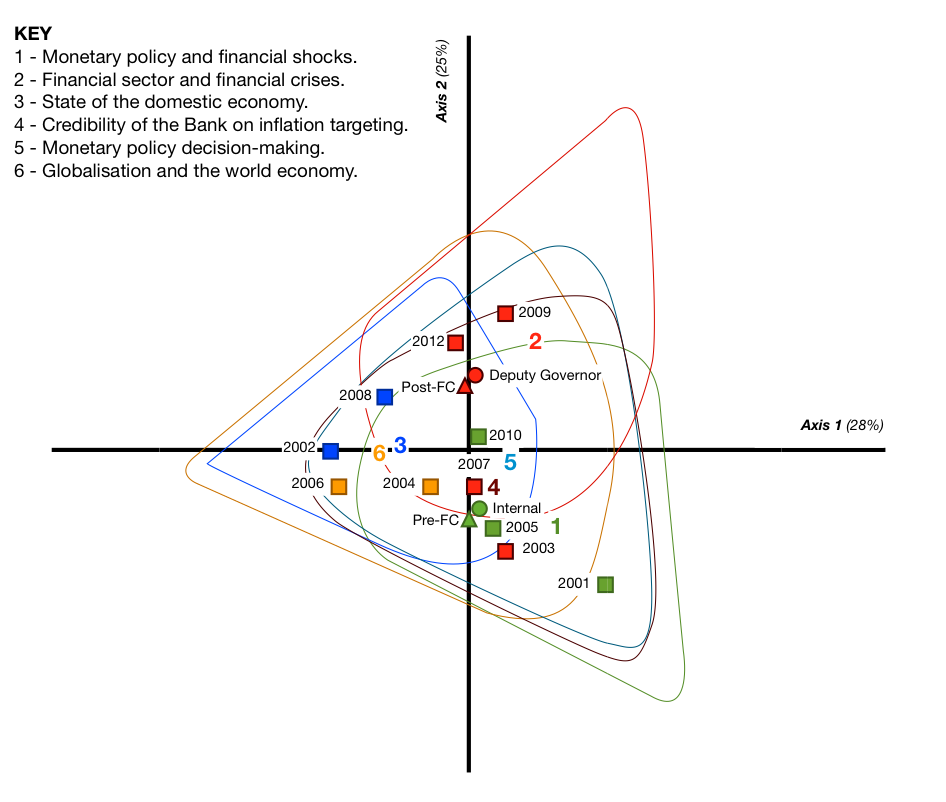

Factor analysis of this corpus shows a distinct shift in the pattern of the discourse (Figure 7). As with all factor analysis graphs presented here, the numbers and outlines represent the associations of classes, and shapes represent the characteristic passive variables. The ‘date’ tags are clearly divided along the vertical dimension, showing a shift in the focus of discourse before and after the ‘flash-point’ of the financial crisis in July 2007. It is plausible that the crisis was the cause of this shift in discourse and observed change in preferences. Again, it seems that the idea of stable preferenceS is contestable, further bringing the effect of the appointment process into question.

The examples highlighted here are simply the ECUs that are most significant to the corpora assessed; a use of a wider data set from broader sources would likely show even more evidence of logical contradictions.

Based purely on this evidence, there is a convincing argument to be made against the concept of stable preferences and against the significance of the appointment process to the MPC’s policy decisions, but further evidence is found elsewhere.

Preference development

Preference development can be understood as strengthening an existing position such that a weak position on an issue or policy action becomes stronger, and that new position does not contradict the earlier position. The member most characteristic of this kind of preference change is Mervyn King.

King’s change is in relation to the level of policy activism necessary to control inflation. In 2004, King seems to take a relatively relaxed attitude to ensuring inflation expectations remain anchored to target:

“It is less likely now that a shock to inflation would lead to a further and persistent deviation of inflation from target. There is a belief that inflation will soon return to target. As a result, a surprise movement in inflation is expected to be temporary and so less likely to lead employers and employees to adjust their desired prices and wages.”

Data 13: King, Oct 2004.

This changes in 2008, when King is seemingly more concerned with the problem of de-anchoring of expectations:

“But there should be no doubt that the MPC is prepared to take whatever action is needed to return inflation to the 2 percent target and to keep expectations of inflation in the medium term anchored to the target.”

Data 14: King, Oct 2008.

Whilst both ECUs here show a concern for inflation expectation anchoring, only the latter emphasizes the degree of policy activism necessary to achieve it. This is likely due to the scale of inflation at the time; in 2004, inflation was within 1% of the target, yet in 2008 reported inflation was over 1% higher than the target of 2.0% and rising. We might view the prevailing conditions as having prompted this preference change.

Arguably, this is only very limited evidence of this kind of preference change; one of the problems with observing a development in a view is that, unlike with a logical contradiction, the researcher must make more subjective judgments about the kinds of language, and the various strengths of the lexis within ECUs and surrounding text. This is particularly difficult with semantic fields such as economic policy, as the language use is likely to be very sterile due to the high levels of technical jargon involved in explaining policy stances. Ultimately, it is easier to spot a contradictory statement than it is to spot one that is of a kind. None-the-less it seems again preferences are unlikely to be as stable as others have suggested.

Preference stability

Preference stability can be considered as a reaffirmation of a pre-existing view; this is distinct from preference development in that this stability should not exhibit a change in the substantive strength of argument. I find strong evidence of preference stability in several members assessed.

Andrew Sentance is one example and shows stability through his views on the basics of the inflation-targeting framework; he consistently reiterates the importance of inflation targeting over the “medium term”.

“Rather, this is a time when we need to stick to the basics of monetary policy – targeting price stability, using the well-established processes of the MPC, focussing on the real economy and taking a medium-term, forward-looking perspective.”

Data 15: Sentance, Sept 2008.

“The UK Monetary Policy Committee quite rightly has an emphasis on the medium-term. […]”

Data 16: Sentance, Nov 2011.

On the topic of credibility, Sentance shows similar stability with strong warnings about the eroding credibility of the MPC:

“If we are not able to do that, the credibility of the framework and the target will be undermined. […]”

Data 17: Sentance, Apr 2008.

“If we continue to experience above-target inflation, while the MPC sets policy to head off the opposite risk – of deflation, confidence in the inflation target and the credibility of the MPC risk being eroded.”

Data 18: Sentance, Oct 2010.

“I do worry that the MPC’s credibility and commitment to the inflation target may already have been eroded by not adjusting policy settings soon enough […]”

Data 19: Sentance, Apr 2011.

Sentance values the importance of credibility very highly – and consistently so. There is obvious preference stability in this case; a preference that the MPC takes action to ensure its credibility. Arguably these ECUs also show development but that would depend on a subjective interpretation of the strength of language used.

Edward George is probably the best example of a member that shows stable preferences, showing stability across most of the areas that the corpus touches upon. The ECUs reveal a consistent view that George believes price stability is not an “end in itself”, often with identical phrasing.

“[…] In this sense price stability is not simply an end in itself. Our aim, like yours in the Eurozone …”

Data 20: George, Feb 1999.

“But it is important to understand that effective price stability would not be intended simply as an end in itself…”

Data 21: Sentance, Apr 2011.

George also has a constant focus on the imbalances between the internationally-exposed and the domestically-oriented sectors of the economy, caused by an appreciation in the value of Sterling. This position is stable across several years, from at least 1998 to 2002:

“Nor does it mean that we simply ignore the plight of the adversely affected sectors. We are concerned – as you are – with the health of every sector of the economy, we fully appreciate the interdependence of the different sectors, […]”

Data 22: George, May 1999.

“And that in effect is what we have done through our recent interest rate cuts. This approach is not, however, without risks. It involves accepting – at least while the dampening external influences persist – a growing imbalance between the internationally-exposed and the domestically-oriented sectors.”

Data 23: George, Jun 2001.

Over a long period of time, George reasserts the view that there is very little the MPC can do to protect the internationally-exposed sectors of the economy. The MPC can only promote growth among the domestically-oriented sectors – even at those other businesses’ expense. This is reiterated over many years and shows a clear preference influenced by the perceived limits of monetary policy.

These are not the only areas in which George shows preference stability but these are perhaps some of the most enlightening. Other examples include views on the appropriateness of political accountability, transparency of the operations of the bank and the inflation target itself; a view shared by Mervyn King.

The examples highlighted here are only typical of those found across all members but are some of the most representative of the prior expectations. A broader view of the ECUs shows preference change beyond pure monetary policy matters as well; Mervyn King constantly reiterates the risks of bank recapitalisation in the wake of the financial crisis, for example. Despite the apparently conflicting evidence of both preference change and stability, there is still clear evidence to suggest that preferences can change; the idea that the appointment process can influence policy outputs is apparently less plausible than others have posited.

Remaining members

The members yet to be mentioned (DeAnne Julius, Sushil Wadhwani, and Christopher Allsopp) did not fit into one of the three prior categories, and showed little clear evidence at all.

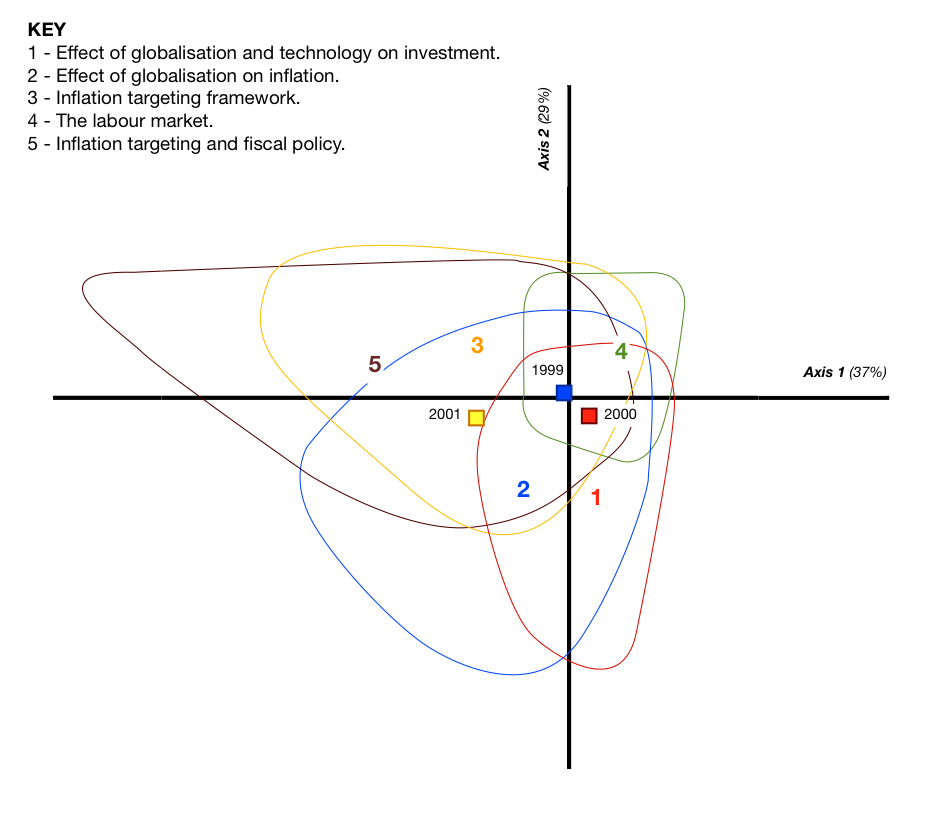

Julius and Wadhwani have very little coherence in the topics they discuss in their respective corpora. The Alceste classifications show five distinct classes for Julius and four for Wadhwani. They broadly cover the same areas but an examination of the data by cross-data analysis doesn’t show as rich a picture as other members. Using Julius as an example, the results highlight a focus primarily on IT as a driver of growth and inflation in 1999, and then a complete topic change in 2001 to discuss globalisation and international factors affecting the economy (Figure 12). A clear shift along the horizontal dimension is observed, moving away from Class 1 toward Class 5 in 2001; this represents a move away from talking about the real economy and ‘big-picture’ statistics, and instead focusing explicitly on the empirics of inflation-targeting. A similar pattern occurs for Wadhwani – though the diagrams are not comparable due to the unique datasets.

| Association | Cumulative | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Axis 1 (left to right) |

Inflation vs real economy |

37% | 37% |

| Axis 2 (top to bottom) |

Domestic vs global |

29% | 66% |

If, as previously discussed, we view the formation of preferences as an acceptance or rejection of arguments later aggregated to form an opinion, then such drastic change in the focus of the discourse could be evidence of preference change but, more plausibly, the results are inconclusive. The notion of multiple factors aggregating to one singular preference – or even multiple underlying preferences – is not incompatible with these results but it is not clear how they interact in these cases. It is also worth noting that these shifts occur either side of the ‘burst’ of the dot-com bubble in 2000; this may have precipitated the change in focus.

The case of Christopher Allsopp is a unique one. The data used in this instance is very small comparatively. Alceste is able to analyse, reliably, corpora of around 10,000 words or higher, and in this instance, the corpus was almost twice this minimum. However, the corpus only comprises two ICUs and neither the cross-data analysis, nor the factor analysis, shows a result indicative of the hypothesis or otherwise. The topics from the corpus are largely unrelated across time, which is likely why very few coherent results are found.

Other evidence

Charles Bean and Mervyn King both present further evidence in favour of the hypothesis, though not in the terms previously theorised. Rather than show change explicitly, both members reference the implicit effects of a committee structure to their decision-making (and thus preference forming) process:

“… Of course, the environment here is a long way from that inhabited by the MPC, but the results are certainly consistent with my own perception of the value of having a committee make the monetary policy decisions.”

Data 24: Bean, Oct 2003.

“… It is important that our views are known to each other before we cast our votes because that is part of the process of making up our mind.”

Data 25: King, May 2002.

“This is the motivation behind the MPC and explains its two key features. First, it is a committee of experts who, before making their decision, discuss their interpretation of the economic data and learn from each other.

[…] The greatest debate among the Committee usually occurs during the quarterly forecast round which often stimulates fresh thinking.”Data 26: King, May 2007.

Both members endorse the idea that decision-making by committee has inherent value. They claim that the committee enables members to update their opinions and preferences, and make more informed decisions. Whilst this doesn’t show evidence of preference change as I previously outlined, it is nonetheless significant that members explicitly make note of this. Taken together with the prior evidence, there is clear support for the hypothesis; preferences can change.

Discussion

Overall, there seems to be clear evidence for the hypothesis. There are a number of points that can be drawn from this.

Firstly, preference change and stability need not be mutually exclusive. Members such as Mervyn King and Andrew Sentance exhibit evidence of both preference change and also preference stability; we should not view this as inherently contradictory but instead as confirmation that preferences are complicated and an amalgam of underlying variables, as previously discussed. Moreover a change in preferences, or indeed stability, may not correspond to changes in actions – voting records do not and cannot capture these underlying changes. This lends weight to the methodology of content analysis used in this paper but more broadly poses a challenge to future research to find better ways than pure statistical modelling to uncover these kinds of political science phenomena.

Interestingly, and in contestation of prior research, there seems to be very little pattern to which types of members experience preference changes. The literature has suggested that those with long-held or extreme views will experience very little preference change (Barabas 2004); certainly, this is true for some members such as Edward George. But at the same time there is evidence that hawks, doves and centrists alike can exhibit preference change too; this evidence runs contrary to this prior thinking on members with policy positions at the extreme. This may be a limitation of the methodology or the size of dataset assessed, but certainly there is room for further exploration here. One consistent pattern is that many changes tend to occur in the wake of major events such as the financial crisis. It does appear that, confronted with a failure in policy, individuals on the MPC will change their preference forming calculations to adopt new arguments and reject old ones; be that to strengthen or to contradict their previous opinion. This would seemingly lend support to the critical junctures thesis discussed earlier and again is a useful avenue for further exploration.

One concern with using case studies, and particularly the MPC, is that findings may be representative of this case but may not apply in other cases. The Bank of England is an old institution and the Bank has employed many MPC members for decades. Because individuals are so used to working within pre-existing structures of the institution, their results might only be applicable to those unique structures. This data set should not suffer significantly from these concerns as both internally appointed and externally appointed members were assessed, and those assessed in-depth were on the committee for different lengths of time. It would not be a significant leap of faith to hypothesise that any central bank with a committee decision-making structure would have the potential to exhibit similar results to those found here.

In terms of the reliability of data and results more broadly, the picture becomes less clear. The dataset is imperfect in-so-far-as it relies on proxies but moreover relies on pre-approved (and likely edited) speeches and articles, rather than verbatim speech like in other studies that have used transcripts. We do not know how much control individuals have over writing of the material assessed in this paper. Moreover, we do not know if members have gone ‘off-script’ in a substantive way during speeches as the data are not, in general, transcripts of speeches but pre-prepared publications of the speeches. The potential for data bias is therefore very possible.

Any bias, however, would likely be tilted toward showing the Bank as a unified voice, despite declarations to the contrary that debate is part of the benefit of the committee. Finding any evidence in support of the hypothesis under these circumstances is therefore significant. Other case studies may well find more convincing evidence but given how insular the Bank of England is when compared with institutions like the Federal Reserve, the scale of evidence that is discernable from this limited dataset is encouraging.

The fact that members also explicitly recognise the benefits of committee decision-making and state that they change how they think based on what others say and argue should also not be underestimated. This is a rare example where the evidence of the ability (or at least willingness) of policymakers to update their opinions could be no clearer.

Overall, I believe there is a strong and evidenced support for the hypothesis. Preferences are not necessarily ‘reasonably stable’ as asserted by prior theorists and instead they can and do change over time.

Returning to the originally posed problem, the implication of this conclusion is clear; the appointment process must matter to some extent to policy outputs on the MPC because I find evidence of preference stability. However, given that I also find significant evidence of preference change, the significance of the appointment process must be overstated in previous literature.

Implications and conclusions

This paper set out to explore the significance of the appointment process to the policy outputs of monetary policy committees, taking the case of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee. At the start of the paper I argued that if we were able to make the assumption that the underlying monetary policy preferences of policymakers were inherently stable, then the significance of the appointment process could be severe. If the appointment process was centred on one, political individual – such as the Chancellor of the Exchequer, then the credible commitment of central bank independence would be an illusion and this paper would help to expose an inconvenient truth.

What I have found is that this assumption is not necessarily true. Members preferences can and do change, and these changes are unpredictable. As a result, so are the actions of those actors. The importance of the MPC’s appointment process to its policy outputs is not necessarily as clear as previously theorised. Whilst it is somewhat inevitable that different kinds of appointment processes will make a difference in some way, the relationship previously highlighted by Hix et al. (2010) is clearly far from certain. The problem with the asserted relationship is two-fold; first it presupposes that the Chancellor has reliable information about a member’s underlying preferences before appointment, and then supposes those preferences remain stable. My evidence suggests that these preferences can change very suddenly and easily, especially during times of economic turbulence.

The evidence presented in this paper has further shown the lack of clarity and loss of information inherent in pure statistical, quantitative analysis; the data must be contextualised in order for us to make any meaningful conclusions. Equally, whilst the methodology in this paper can tell us a great deal, it cannot tell us the significance of the appointment process in absolute terms. Future research may wish to combine the benefits of raw statistical modelling with content analysis in some way to try to better explain the link between appointments and policy outputs.

For the appointment process to significantly matter to the outputs of a monetary policy committee, we need to be able to hold certain factors – like the behaviour of policymakers under identical conditions – constant. What this paper has highlighted is that ultimately the appointment process will matter, but preferences can change and so we still can’t tell how much.

Appendix 1: Members of the MPC

| Member | Tenure Start | Tenure End | Included? | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Howard Davies | 1997 | 1997 | No | No speeches. Less than 2 years membership. |

| Alan Budd | 1997 | 1999 | No | Less than 2 years membership. |

| Williem Buiter | 1997 | 2000 | Yes | |

| Charles Goodhart | 1997 | 2000 | Yes | |

| DeAnne Julius | 1997 | 2001 | Yes | |

| Ian Plenderleith | 1997 | 2002 | Yes | |

| David Clementi | 1997 | 2002 | Yes | |

| Edward George | 1997 | 2003 | Yes | |

| Mervyn King | 1997 | 2013 | Yes | Current member, but more than 2 full terms membership. |

| John Vickers | 1998 | 2000 | Yes | |

| Sushil Wadhwani | 1999 | 2002 | Yes | |

| Christopher Allsopp | 2000 | 2003 | Yes | |

| Stephen Nickell | 2000 | 2006 | Yes | |

| Charles Bean | 2000 | 2013 | Yes | Current member, but more than 2 full terms membership. |

| Kate Barker | 2001 | 2010 | Yes | |

| Marian Bell | 2002 | 2005 | Yes | |

| Andrew Large | 2002 | 2006 | Yes | |

| Paul Tucker | 2002 | 2014 | Yes | Current member, but more than 2 full terms membership. |

| Richard Lambert | 2003 | 2006 | Yes | |

| Rachel Lomax | 2003 | 2008 | Yes | |

| David Walton | 2005 | 2006 | No | Less than 2 years membership. |

| John Gieve | 2006 | 2009 | Yes | |

| David Blanchflower | 2006 | 2009 | Yes | |

| Tim Besley | 2006 | 2009 | Yes | |

| Andrew Sentence | 2006 | 2011 | Yes | |

| Spencer Dale | 2008 | 2013 | No | Current member, less than 2 full terms membership. |

| Adam Posen | 2009 | 2012 | Yes | |

| Paul Fisher | 2009 | 2014 | No | Current member, less than 2 full terms membership. |

| David Miles | 2009 | 2015 | No | Current member, less than 2 full terms membership. |

| Martin Weale | 2010 | 2013 | No | Current member, less than 2 full terms membership. |

| Ben Broadbent | 2011 | 2014 | No | Current member, less than 2 full terms membership. |

| Ian McCafferty | 2012 | 2015 | No | Current member, less than 2 full terms membership. |

Appendix 2: Corpus preparation

Corpora must be formatted in specific ways for successful analysis using Alceste; first, by removing data that might distort the analysis and second, attaching passive variables to the ICUs.

Most special characters cause the Alceste analysis to fail. Table 6 shows which characters were removed or replaced to ensure successful analysis.

| Removed | Symbol(s) | Replaced with |

|---|---|---|

| Currency | £ $ € | GBP USD EUR |

| Punctuation | - * : ; () [] “” ‘’ ’ | – |

| Math | % | percent |

| Bullets | • | N/A (removed without replacement) |

Footnotes or endnotes were excluded from the analysis; these data tended to be purely technical and/or referencing, and so would not have added any real insight to the data. Images, graphs and tables were also removed as Alceste cannot process this data.

The passive variables for each ICU identified the speaker/author, their ‘dove-hawk’ classification based on Hix et al (2010), the member’s committee role, the date and the ICU’s relative position to the financial crisis, taking July 2007 as the start of the crisis. Table 7 shows the passive variables used.

| Tag | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| *N_ | Name | e.g. King |

| *P_ | Position | Governor, Deputy Governor, Internal, External |

| *HD_ | Hawk-Dove | Hawk, Dove, Centrist |

| *M_ | Month | e.g. January |

| *Y_ | Year | e.g. 2010 |

| *FC_ | Financial crisis | Pre, Post |

In general, researchers attempt to standardise language across corpora by changing acronyms to words, etc. However, I could not be confident that a simple ‘find and replace’ in the data would maintain the integrity of the corpus. As an example, the Monetary Policy Committee is also referred to as ‘the committee’ and ‘the MPC’. However, there are multiple committees referenced in the corpus meaning a simple replacement of the word ‘committee’ would be inappropriate. Moreover, MPC could also be referring to a different abbreviated term; in economics literature ‘mpc’ can mean ‘marginal propensity to consume’, for example. To maintain coherence in the text I left all abbreviated terms and acronyms in place. This did not seem to hinder the analysis significantly as many of these terms still gained high Chi-squared values in the results.

Appendix 3: Classifying Adam Posen

Adam Posen was not included in the original Hix et al. (2010) dataset; he was appointed in 2009, and their dataset finishes in 2008. I used this dataset as a starting point for my analysis as it initially provided a simple way of understanding members’ preferences but this meant Posen needed to be included in one of the three catagories. Ultimately, my results were unlikely to significantly change based on where Posen was classified as I was interested in individuals, so a rough classification was deemed sufficient for this paper.

To gain this insight, I conducted a review of UK press media, including the Financial Times, BBC, Economist, and others and informally discussed the issue with Prof. Simon Hix. When questioned on 21 March 2013, Hix’s response was “oh, definitely a dove”, and this view was shared by every news source that I viewed that mentioned Posen’s time on the MPC. Some even went as far as describing him as an “arch-dove” (Chu 2011, Anonymous 2011a).

Whilst this classification is imprecise, it is precise enough for the purposes of providing a broad direction to the rest of the paper.

Appendix 4: Alceste Classes – Hawks, Doves and Centrists

| Sig' member (Chi2, Rank) |

Significant present forms (Chi2, Rank) |

Significant absent forms (Chi2, Rank) |

Used? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hawks | ||||

| Domestic growth and employment | Sentance (273, 2) | survey (407, 1), unemployment (227, 3), show (223, 4), GDP (219, 4), recession (196, 6) | policy (-144, 3), monetary (-116, 4), inflation (-92, 5), risk (-59, 8) | No |

| State of the global economy | Sentance (146, 15) | global (266, 1), asia (247, 2), china (237, 3), commodit (232, 4), strong (214, 5), emerg (209, 6) | policy (-117, 3), monetary (-90, 4), bank (-65, 6), target (-56, 8) | No |

| Stability of the financial sector | Large (1419, 1) | stabil (208, 7), system (182, 9), area (168, 10), standard (155, 11), threat (149, 12) | inflation (-150, 4), econom (-144, 5), growth (-110, 7) | No |

| Monetary policy framework | Sentance (234, 8) | inflation (769, 1), policy (715, 2), monetary (643, 3), target (351, 4), MPC (258, 7) | show (-87, 6), market (-80, 8), chart (-75, 9), manufactur (-70,10) | Yes |

| Risk in the financial system | Large (727, 1) | transfer (254, 5), liquid (250, 6), hedge (166, 8), collateral (145, 9), bank (143, 10), debt (139, 11) | inflation (-100, 4), econom (-77, 5), growth (-57, 7), UK (-44, 8) | No |

| Consumption and credit availability | Besley (211, 8) | household (790, 1), income (645, 2), consumption (424, 3), saving (366, 4), house (323, 5) | global (-40, 3), inflation (-40, 4), policy (-33, 5), monetary (-27, 6) | No |

| Centrists | ||||

| Responses to the financial crisis | Tucker (1303, 1) | liquid (1294, 2), system (1025, 4), bank (943, 5), capital (789, 6), financ (576, 8), fund (572, 9) | inflation (-1002, 2), rate (-530, 3), growth (-356, 4) | No |

| Operations of the MPC | King (158, 26) | member (704, 1), decision (433, 2), committee (399, 3), governor (310, 4), I (290, 5) | demand (-271, 2), fall (-260, 3), growth (-226, 4), rise (-221, 5) | Yes |

| State of the economy | George (481, 9) | growth (1140, 1), year (700, 2), domestic (591, 3), econom (582, 4), inflation (290, 24) | bank (-629, 1), system (-283, 3), liquid (-222, 4), financ (-181, 5) | Yes |

| Monetary policy framework | Bean (566, 1) | inflation (448, 2), nominal (445, 3), chart (426, 6), rate (351, 7), household (332, 8) | system (-236, 3), bank (-204, 4), international (-144, 5), I (-133, 6) | Yes |

| Doves | ||||

| Explaining exchange rate fluctuations | Wadhwani (1403, 1) | exchange (1131, 2), sterling (477, 4), rate (389, 6), model (309, 8), equilibrium (222, 9) | bank (-53, 10), worker (-47, 12), employ (-45, 13), labour (-44, 14) | Yes |

| Monetary policy in academic perspective | Posen (456, 1) | central (255, 6), policy (181, 9), independence (124, 15), right (123, 16), monetar (105, 17) | rate (-79, 3), percent (-64, 4), unemploy (-50, 5), product (-47, 6) | Yes |

| Competitiveness | Wadhwani (754, 3) | product (1197, 1), internet (494, 4), competition (393, 6), ICT (365, 8), growth (342, 9) | policy (-53, 8), bank (-46, 11), monetar (-41, 13), rate (-37, 17) | No |

| Monetary policy implementations | Allsopp (1259, 1) | function (560, 3), react (549, 4), policy (549, 5), monetar (531, 6), target (519, 7) object (307, 8) | unemploy (-44, 5), year (-31, 7), fall (-30, 8), product (-29, 9) | Yes |

| Determinants of inflation | Julius (28, 65) | price (364, 1), pressure (305, 2), oil (293, 3), capacit (276, 4), inflation (264, 5), spare (211, 6) | bank (-36, 2), policy (-30, 3), monetar (-24, 4), find (-19, 5) | Yes |

| Employment statistics | Blanchflower (904, 3) | self-employment (498, 5), data (316, 7), individual (301, 8), probabilit (301, 9), dumm (276, 10) | econom (-70, 4), policy (-61, 5), monetar (-38, 16), fall (-37, 18) | No |

| Wages and employment | Blanchflower (911, 2) | worker (697, 3), unemploy (595, 4), employ (342, 5), labour (283, 6), number (247, 7), job (184, 13) | inflation (-164, 3), policy (-105, 5), monetar (-92, 8) | No |

| Lessons from Japan asset bubble | Posen (868, 1) | japan (448, 3), fiscal (353, 5), estate (236, 6), crisis (233, 7), boom (223, 8), recession (213, 9) | inflation (-38, 7), unemploy (-29, 11), exchange (-24, 12) | No |

| The financial sector | Posen (473, 6) | lend (670, 1), credit (646, 2), bank (539, 4), assets (535, 5), securit (419, 8), purchase (357, 9) | inflation (-73, 4), rate (-38, 8), percent (-35, 9) | No |

Bibliography

Anonymous (2010a) ‘A monetary policy committee divided’, Financial Times, 21 October 2010, 18.

Anonymous (2010b) ‘Hawk v Dove – the MPC dilemma’, The Telegraph [accessed 10 Janary 2013].

Anonymous (2011a) ‘Bank of England MPC: Who sets interest rates?’, BBC News Business[accessed 10 Janary 2013].

Anonymous (2011b) ‘Policy dilemma’, Business Europe, 51(1), 2-3.

Bailey, A. and Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2008) ‘Does Deliberation Matter in FOMC Monetary Policymaking? The Volcker Revolution of 1979’, Political Analysis, 16(4), 404-427.

Bailey, A. and Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2010) ‘Deliberation and Oversight in Monetary Policy, 1976-2008’ (chapter of forthcoming monograph, Deliberating Monetary Policy), conference paper, presented at Southern Economic Association Annual Meeting, Atlanta, 20-22 November 2010, 2-48.

Bailey, A. and Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2013, forthcoming) Deliberating American Monetary Policy: A textual analysis, MIT Press.

Bank of England (2011) ‘Inflation Report’, Bank of England [accessed 15 January 2013].

Bank of England Act 1998, c.11, United Kingdom: Stationery Press.

Barabas, J. (2004) ‘How Deliberation Affects Policy Opinions’, American Political Science Review, 98(4), 687-701.

Barro, R. J. and Gordon, D. B. (1983) ‘Rules, discretion and reputation in a model of monetary policy’, Journal of Monetary Economics, 12(1), 101-121.

Baumgartner, F. R. and Jones, B. D. (2002) Policy dynamics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 293-306.

Bean, C. and Jenkinson, N. (2001) ‘The formulation of monetary policy at the Bank of England’, Bank of England. Quarterly Bulletin, 41(4), 14. 434-441.

Blinder, A. S. (2007) ‘Monetary policy by committee: Why and how?’, European Journal of Political Economy, 23(1), 106-123.

Blinder, A. S. and Morgan, J. (2005) ‘Are Two Heads Better Than One? Monetary Policy By Committee’, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 37(5), 798-811.

Brown, G. (2003a) Remit for the Monetary Policy Committee, April 2003, HM Treasury [accessed 20 March 2013].

Brown, G. (2003b) Remit of the Monetary Policy Committee and the New Inflation Target, December 2003, HM Treasury [accessed 20 March 2013].

Chang, K. H. (2003) Appointing Central Bankers: The Politics of Monetary Policy in the United States and the European Monetary Union, Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions, New York: Cambridge University Press, 37-90.

Chu, B. (2011) ‘Posen urges bankers to prevent second recession’, The Independent (Business) [accessed 10 January 2013].

Chubb, J. E. (1988) ‘Institutions, the Economy, and the Dynamics of State Elections’, The American Political Science Review, 82(1), 133-133.

Cukierman, A., Web, S. B. and Neyapti, B. (1992) ‘Measuring the Independence of Central Banks and Its Effect on Policy Outcomes’, The World Bank Economic Review, 6(3), 353.

Fincher, C. (2011) ‘Factbox – Bank of England doves in ascendancy’, Reuters UK [accessed 10 March 2013].

Hall, P. A. and Taylor, R. C. R. (1996) ‘Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms’, Political Studies, 44(5), 936-957.

Hayek, F. A. and Klausinger, H. (2012) Business Cycles, Chicago: Chicago University, 45-166.

Hix, S., Høyland, B. and Vivyan, N. (2010) ‘From doves to hawks: A spatial analysis of voting in the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England’, European Journal of Political Research, 49(6), 731-758.

Jones, B. D. (2003) ‘Bounded Rationality and Political Science: Lessons from Public Administration and Public Policy’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 13(4), 395-412.

King, M. (2005) ‘Epistemic Communities and the Diffusion of Ideas: Central Bank Reform in the United Kingdom’, West European Politics, 28(1), 94-123.

Kronberger, N. and Wagner, W. (2000) ‘Keywords in Context: Statistical Analysis of Text Features’ in Bauer, M. W. and Gaskell, G., (eds.), Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook, London: SAGE, 299-317.

Kydland, F. E. and Prescott, E. C. (1977) ‘Rules Rather than Discretion: The Inconsistency of Optimal Plans’, Journal of Political Economy, 85(3), 473-491.

Lindblom, C. E. (1959) ‘The Science of “Muddling Through”‘, Public Administration Review, 19(2), 79-88.

Lombardelli, C., Proudman, J. and Talbot, J. (2005) ‘Committees Versus Individuals: An Experimental Analysis of Monetary Policy Decision Making’, International Journal of Central Banking, 1(1), 181-205.

Marcussen, M. (2005) ‘Central banks on the move’, Journal of European Public Policy, 12(5), 903-923.

Mattich, A. (2011) ‘Bank of England Dove’s Threat Highlights Lack of Accountability’, The Wall Street Journal (The Source) [accessed 10 January 2013].

McNamara, K. (2002) ‘Rational Fictions: Central Bank Independence and the Social Logic of Delegation’, West European Politics, 25(1), 47-76.

Meade, E. E. (2005) ‘The FOMC: Preferences, Voting, and Consensus’, Review – Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 87(2), 93-101.

Moser, P. (1999) ‘Checks and balances, and the supply of central bank independence’, European Economic Review, 43(8), 1569-1593.

Nordhaus, W. D. (1975) ‘The Political Business Cycle’, The Review of Economic Studies, 42(2), 169-190.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2012) ‘Main Economic Indicators (Edition: November 2012)’, OECD [accessed 15 January 2013].

Rogoff, K. (1985) ‘The Optimal Degree of Commitment to an Intermediate Monetary Target’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 100(4), 1169-1189.

Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2005) ‘Measuring Ideas More Effectively: An Analysis of Bush and Kerry’s National Security Speeches’, PS: Political Science & Politics, 38(4), 701-711.

Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2008) ‘The Congressional Debate on Partial-Birth Abortion: Constitutional Gravitas and Moral Passion’, British Journal of Political Science, 38(3), 383-410.

Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2010) ‘Problems and solutions in displaying results from Alceste’, [accessed March 2013].

Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2012) ‘Looking at Congressional Committee Decisions from Different Perspectives: Is the Added Effort Worth It?’, conference paper, presented at 5th ESRC Research Methods Festival, St Catherine’s College, Oxford, 2-5 July 2012, 1-39 .

Schonhardt-Bailey, C., Yager, E. and Lahlou, S. (2012) ‘Yes, Ronald Reagan’s Rhetoric Was Unique—But Statistically, How Unique?’, Presidential Studies Quarterly, 42(3), 482-513.